Residence registration is an important element of public administration which is used for population statistics, fiscal redistribution, administrative and social service provision, organizing elections, administration of justice, official correspondence, and investigation. The lack of common practice of registering one’s place of residence leads to inefficient use of budget funds and limits the population’s access to government-guaranteed services. The current system of residence registration fails to accomplish its functions due to the complicated procedure which creates obstacles for those people who live in households not owned by them or their family members. In the current situation, the effective strategy for reforming the residence registration would be to implement a fully declarative system.

In the Soviet period, the institute of registration (so called “propiska”) played an important role in the process of production planning by controlling the allocation of workforce. After Ukraine declared independence, registration in its Soviet form was deemed unconstitutional because it infringed on human rights. After the Ukrainian Law “On the freedom of movement and the free choice of the place of residence in Ukraine” had been passed in 2003, it was supposed that the system of permissions would be replaced by declarative system of residence registration. However, in practice, the transition to the fully declarative system has never been accomplished. As a result, a major share of the population do not register their actual places of residence. According to a study by the NGO Territory of Success in 2011, approximately a third of the surveyed in regional centers do not live at their registered place of residence. And according to a complex estimate by the Institute of Demographics of the National Academy of Science, about 13% of the de facto population of Kyiv do not live at their registered residence.

As a result, the residence registration fails to properly perform its functions in the system of government administration.

➢ Distorts the state statistics about the spatial distribution of the population

Since a major share of the population do not register their actual place of residence, the registration records do not reflect the real population movement. Thus it fails to properly play its role in the current population estimates between censuses. Given that the last census was carried out in 2001, there can be considerable inaccuracies in the data about population numbers on the territories with high mobility rates.

➢ Creates disproportions in local budget revenues

A share of the income tax paid at a given territory is part of local budget revenues. Individual entrepreneurs pay a local tax – the single tax – at the place where they are registered as taxpayers (which is often the same as their place of registered residence). The regional fiscal equalization (the basic and the reverse subsidies), as well as the healthcare subvention are distributed according to the number of registered population. Inaccurate numbers of population in some territories leads to a situation when the amounts of redistributed funds do not correspond to the actual needs of the region. This problem will only get worse as the decentralization develops further, and more and more of the government functions are passed on to the local level.

➢ Limits the population’s access to administrative services, including social ones

Due to the lack of electronic registers, a considerable number of administrative services, as well as some social services are still provided only at the registered place of residence. As a result, the population who do not live at their place of registration, have to spend more time and resources to obtain services in the settlement where they are registered. Although the process of introducing electronic registers has already started (in particular, the Unified State Demographic Register is being filled in, and some registers of receivers of social services are being modernized), it progresses slowly. In addition, due to objective reasons, some services can only be provided at the place of registration.

➢ Limits the population’s access to health care

Due to the particularities of health care funding, access to services in state outpatient clinics which do not correspond to one’s registered place of residence could be complicated by bureaucratic obstacles. As a result persons who do not live at their registered residence avoid going to outpatient clinics. In addition, this situation creates favorable conditions for everyday corruption.

➢ Limits the rights of unregistered community members to elect local governments

The citizens who do not live at their registered residence cannot participate in local elections and elect their representatives in the communities where they live.

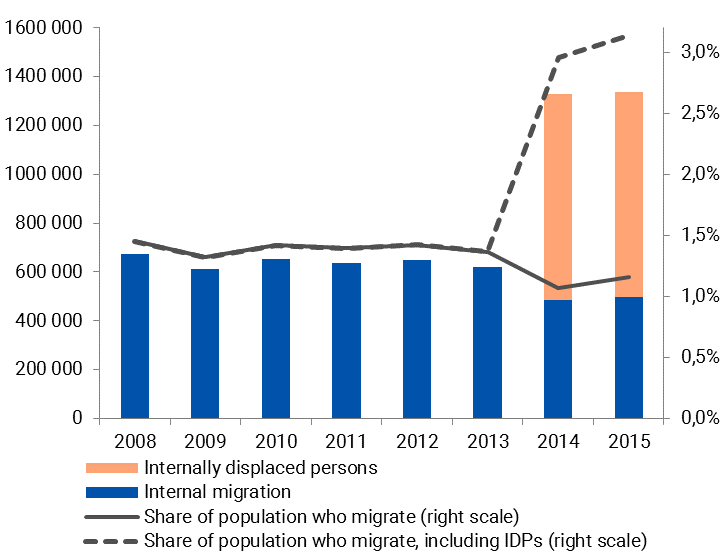

These problems have become especially urgent after a major wave of internally displaced persons. According to the official data, in 2014-2015, forced migration numbers were double the numbers of internal migration (see Fig.1).

Fig. 1. Internal and forced migration

The inflexible system of residence registration became the reason why the most mobile population groups have limited access to health care, have difficulties with receiving administrative services and cannot vote at local elections.

Why, despite the abovementioned inconveniences, a considerable share of the population do not register their place of residence? To a large extent, this can be explained by the requirements for registration. In order to register one’s palace of residence, one has to prove their right to live in the dwelling . According to the law, there is a list of documents that can prove the right to reside in the dwelling and could serve as a ground for registering a place of residence. If these papers are lacking, the registration is possible only after the consent of the owner(s) of housing unit. In fact, local government bodies and their service provision centers require owner consent in all cases of registration, including the cases based on rent contracts.

In addition, there is a widespread stereotype that a person registered at a certain dwelling can claim to become an owner of the part of the dwelling. This stereotype together with the mentioned above practices leads to the situation where the system fails to perform its functions, namely, to notify the government about the place of residence where it is convenient for a citizen to obtain administrative services, receive health care, and participate in elections. Since registration depends on the ownership of housing, one can receive a range of government-guaranteed services only in the territorial unit where one has a dwelling to be registered in. Persons who live in housing units which do not belong to them have limited access to these services.

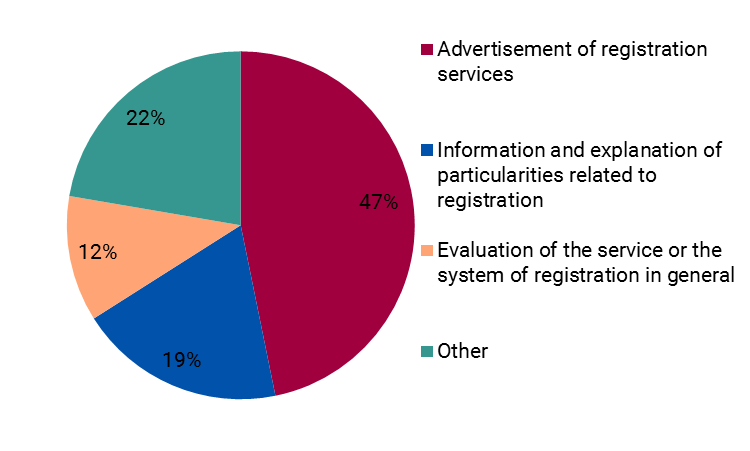

Certain population groups who are not the owners of the housing, find it particularly difficult to register their place of residence. This fact is confirmed by the demand for services of intermediaries who offer, for a fee, to find a place where a client could register for a certain period of time. The evidence for this demand is the availability of extensive supply of “registration purchasing” services in the social media. Based on the analysis of the content on Facebook, VK, and Twitter, we found that 47% of mentions of the topic of registration is advertisement for the services of “registration sellers.”[1]

Fig. 2, The frequency of mentions of the topic of the registration of place of residence in Facebook, VK, Twitter in 2014-16 (%)

If the current system of registration is maintained, the rise of internal mobility will only make the existing problems related to the residence registration ever more serious. Increasing number of people will not have free access to government-guaranteed services. The disproportion between local budget revenues and the actual needs of the territories will increase.

Recommendations

Despite the widespread opinion that “registration is a remnant of the Soviet past” and should be discarded, governments in many countries need information about the place of residence of people who permanently live on their territory. Based on the way countries collect this information, they can be grouped under two categories.

Countries that use residence registration

The use of the registration means that that all citizens should have a special document (an ID, a passport, a separate document confirming registration) in which their permanent address of residence is recorded , and there is a procedure on how to change this address. The recorded place of residence can be used as the tax address and the address where one can receive certain services. In most EU countries, residence registration is used on the national level.

Countries where people notify the relevant authorities of their place of residence

In the countries that do not have the institute of residence registration, people notify the relevant authorities (tax department, election committee, municipality) by themselves. In order to prevent fraud, some services provided at the place of residence require proof of residence (such as personal utility bills for a certain address). This system functions in the US, the UK, Canada, and some EU countries (France, Portugal).

In Ukraine, it is impossible to discard the system of residence registration, since a number of government administration spheres are based on it. The experience of countries which use registration demonstrates that, in post-socialist countries that have reformed the Soviet-type registration system, it is more efficient to use the declarative model of residence registration. According to this model, one is supposed to declare their place of residence by notifying local authorities about their new address, indicating the grounds for the change, but without the need for any confirmatory documents. The declared data can be verified by local governments at their will, but it is not mandatory for the declaration. This model creates incentives to notify the government about the address where one lives, and does not hinder the registration by requiring “documents” or “owner’s consent.” Given that, in Ukraine, the crucial obstacle for registration is the dependence of the possibility to register on the ownership of housing, this model is optimal for reforming the current system of residence registration.

In order to successfully implement the declarative model, the role of the registered place of residence should be reviewed in the following areas: current population statistics, administrative services, local elections, health care, welfare payments, budget transfers.

To the State Migration Service

To ensure that everyone has the opportunity to register their actual place of residence without obstacles by implementing the declarative system of registration.

To the State Statistics Service

To change the methodology of estimation of internal and external migration flows.

To the Ministry of Health Care

To modify the mechanism of healthcare funding based on the principle “money follows the patient.”

To the Ministry of Finance

To review the formulas for interbudgetary transfers which include number of registered population.

To the Central Election Commission

To ensure that all local community members regardless of their place of registration have the right to vote at local elections.

The specific mechanism of declaring one’s place of residence and the plan for further action must be designed in close cooperation between the responsible government bodies and the civil society.

Recommended Literature:

Residence Registration: Challenges for the Government and Implications for the Society. — Kyiv: CEDOS Think Tank, 2017. — 34 pages.

International Experience in the Residence Registration [Electronic Resource] // CEDOS Think Tank. — 2017. — Access: Upcoming at www.cedos.org.ua.

[1] In November 2016, we carried out a content analysis of social media, namely Facebook, VK, and Twitter. We collected all the mentions of the topic of residence registration in posts by users, public pages and in groups in 2014-16. The sample consists of 102 posts.

Support Cedos

During the war in Ukraine, we collect and analyse data on its impact on Ukrainian society, especially housing, education, social protection, and migration