Project: Ukrainian Students Migration to Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, the Slovak Republic: human capital perspectives

Funded by International Visegrad Fund and The Kingdom of the Netherlands

Grant managing organisation: Institute of Public Affairs

Authors: Yana Leontiyeva, Liudmila Kopecká

Concept of the project and methodology of the research: Yegor Stadny, Oleksandra Slobodian, Anastasia Fitisova, Mariia Kudelia

Review: Mariia Kudelia

Table of content

Basic facts and numbers about Ukrainian migration to the Czech Republic

Legal and institutional settings related to foreign students

Migration policies and access to education for foreign students

Recruitment and promotion strategies

Ukrainians students and graduates – numbers, profile, plans

The profile of Ukrainian students and graduates in Czech Republic

Motivation of Ukrainian students to study abroad

The potential of human capital of Ukrainian graduates and students

The strategies after graduation

Attachment 1 – Methodology note

Attachment 2 – In-Depth Interviews Guides

Attachment 3 – Questionnaires for collecting statistics

Attachment 4 – Questionnaire for online surveys

List of abbreviations

AMU Academy of Performing Arts in Prague

BUT Brno University of Technology

CTU Czech Technical University

CU Charles University

CULS Czech University of Life Sciences

CZCO Czech Statistical Office

DZS Centre for International Cooperation in Education

IHM The Institute of Hospitality Management

ILPS CU The Institute for Language and Preparatory Studies, Charles University

KZPS Confederation of Employers' and Entrepreneurs' Associations

MENDELU Mendel University in Brno

MEYS Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic

MFA Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Czech Republic

MoI Ministry of the Interior of the Czech Republic

MoLSA Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs of the Czech Republic

MU Masaryk University

MUP Metropolitan University Prague

UCT Prague University of Chemistry and Technology in Prague

UMPRUM Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague

VŠE University of Economics in Prague

VSFS University of Finance and Administration

Executive summary

-

This report describes legal and institutional settings in the Czech Republic related to student migration in general and explores the main characteristics and strategies of Ukrainian students in particular.

-

Secondary analysis of available documents, statistics and literature was combined with the analysis of qualitative and quantitative data gathered during the project: 16 in-depth interviews with relevant actors involved in the process and an on-line survey with 259 Ukrainian students and 48 graduates from Czech universities. Data on graduates serve rather for orientation purpose.

-

Ukrainians represent the largest group of immigrants in the Czech Republic. Despite the growing trend, student migration seems to be rather marginal component in Ukrainian migration to this country: out of 120 thousand of Ukrainian citizens registered in the Czech Republic only slightly more than 3 thousand were studying at Czech universities in 2017.

-

Given the ongoing and emerging push factors in Ukraine and pull factors in the Czech Republic combined with limited alternative migration strategies Ukrainian student migration is expected to gain importance in the following decades. Despite the increasing trend Ukrainian student migration hasn’t received deserved attention from scholars yet.

-

Ukrainians represent about 7% of all foreign students (outnumbered by Slovaks and Russians). More than three thirds of Ukrainians students attend public universities and vast majority of those at public universities do not pay for their studies because they are attending Czech language study programmes.

-

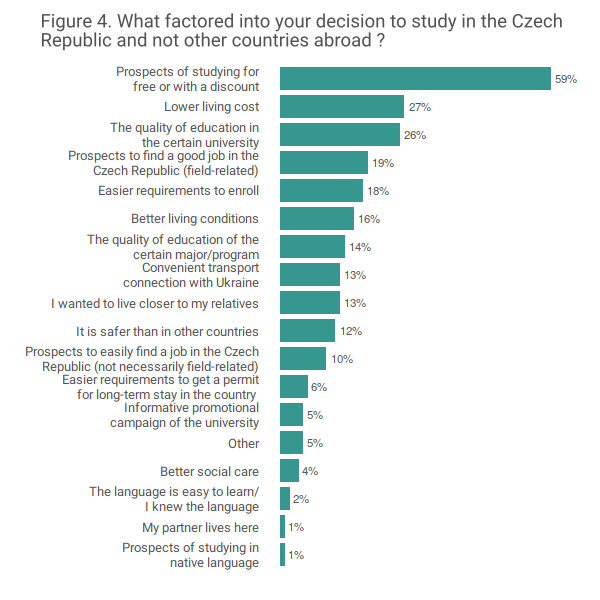

The share of Ukrainian students enrolled in private universities and those studying programs in foreign languages is slightly growing but free of charge access to public education in Czech Language is one of the most important pull factors: it was mentioned as a main reason to come and study in the Czech Republic by 59% of the survey respondents.

-

None of the strategic documents on Czech education or migration policies sets priorities towards certain countries or types of foreign students and the bottom-up approach defines current needs.

-

Most Czech universities don’t have special recruitment strategies for Ukrainian students but they do recognize the potential of Ukrainian student migration (i.e. similar education system and adequate knowledge of applicants, as well as smooth integration due to language and cultural proximity) and mostly report good experience with Ukrainian students.

-

Ukrainian students who study in Czech language at public universities are treated as Czech students not only in terms of access to education and related services but also for the purpose of statistics. The data about Ukrainian students are poor and data about graduates are practically missing.

-

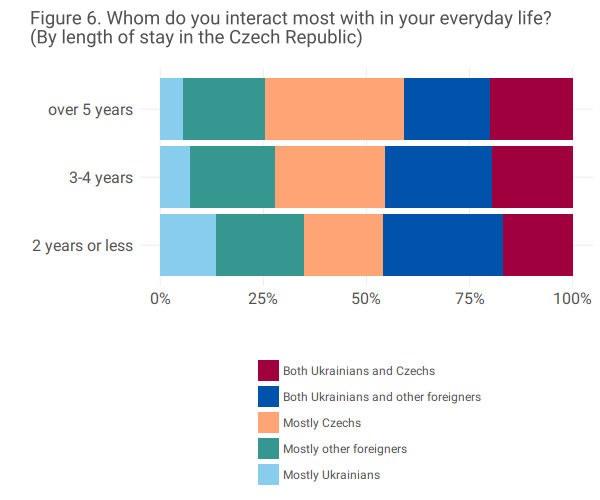

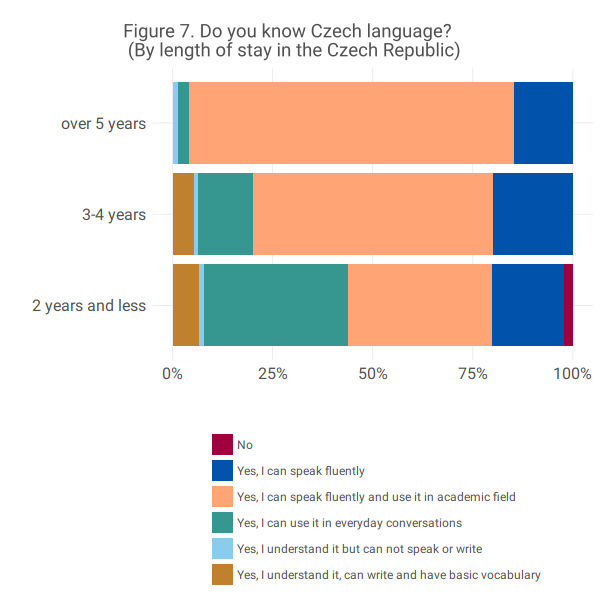

Ukrainian students have very advanced Czech language skills but a significant part of them rely on communication with compatriots and other foreigners (not Czechs).

-

There is no statistics concerning the transition of Ukrainian graduates from education to labour market in the Czech Republic. According to survey Ukrainian students are mostly economically active already during their studies: 67% of current students were working at the moment of the survey and 13% of them used to work before during their studies.

-

Ukrainian students seem to grow roots in the Czech Republic. Not all of them were able to express their plans for the future but inclinations towards remaining in the country of studies seem to be strong: 36 % of current students were not decided about their future yet, 37 % of them plan to stay in the Czech Republic and 19 % plan to move elsewhere (mostly within the EU). The length of stay in the Czech Republic seems to be strongly correlated with the preference to remain here: after 5 and more years of studies almost half of surveyed students plan to stay in the country after the graduation. Only less than one tenth (8 %) of surveyed students intend to return back to Ukraine and after 5 years of studies the preference for return became even less frequent.

-

Those who plan to stay in the Czech Republic after the graduation, as well as the graduates who already stayed here, mentioned better living conditions in the Czech Republic, higher salaries and better job opportunities in given professional field as main reasons to remain in the country.

-

Free access to the labour market for full-time students and graduates in the Czech Republic is an important advantage but the legal status of non-EU citizens after graduation remains uncertain. Especially disadvantaging is the fact that the length of studies is calculated for the purpose of permanent residence permit application only by one half.

-

Growing interest for foreign students (including those from Ukraine) on the side of Czech universities is not only the consequence of socio-demographic development and the lack of Czech students. The importance of internationalization of tertiary education is acknowledged on the strategic level. Yet, political and public debate about the benefits of student migration (including those from Ukraine) and the human potential of foreign graduates seem to be in a very initial stage.

Policies

Introduction

In today’s interconnected world the knowledge of at least one foreign language is considered to be a prerequisite for highly competitive international labour market. Not only language skills but also experience in intercultural communication and ability to understand global connections are often required to build a successful career. International education is therefore seen as a good way of obtaining valuable skills and experiences. Foreign diploma is perceived as a matter of prestige and an important mean for obtaining high socioeconomic status in the countries of origin. In the destination countries foreign students are often treated as highly-skilled immigrants. Universities, language schools, and other educational institutions all around the world promote their services and educational programmers and compete for international students. Having a high share of international students is a matter of prestige and many universities in non-Anglophone destinations make efforts to establish more courses and programs in English language so that they can compete on the global education market with such key destinations like the USA, Great Britain and Australia.

The condition for entering the country, accessing the education and stay in the country after the graduation differ from country to country. Generally student migration is often considered less-problematic by both, public opinion and politicians, therefore immigration laws are usually more favourable towards this type of immigrants, partly because the stay of students is often considered temporary. Migration of students is often problematized as a “brain drain” for source countries and the debate about migration aspirations and strategies of students after the graduation is very intensive all around the world as foreign graduates are considered to be a part of the global mobile elite many countries are competing for.

Recent developments suggest that the Czech Republic is gradually becoming a very attractive destination for foreign students, especially for Slovaks and students from Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Growing interest for foreign students on the side of Czech universities is often put in connection with socio-demographic development resulting in the lack of Czech students. But demographic situation is apparently not the main reason and the need of internationalization of tertiary education is nowadays recognized at the strategic level.

Student migration around the world has been addressed and described by many academics, politicians, as well as by both governmental and non-governmental organizations. Though in the Czech context, despite the increasing number of international students, this type of migration hasn’t received deserved attention from scholars yet. Foreign students are often incorporated into studies of different migrant groups (predominantly from non-EU countries) or in the larger studies of students and graduates (but here the nationality is often not followed). There are few relevant studies focused on student migration to the Czech Republic and dealing with the processes of adaptation of young immigrants to the host country and the new educational system. Most of mentioned studies are however bachelor, master and doctoral theses written by foreign students themselves and mostly dedicated to student migration from Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia. Although there is a number of scientific publications dedicated to Ukrainian migration to the Czech Republic, student migration from this country remains insufficiently research and described.

This report hopes to fill mentioned gap. Its aim is not only to describe the legal and institutional settings in the Czech Republic related to student migration in general but most importantly to explore the main characteristics and the strategies of Ukrainian students. The report is based on secondary analysis of available documents and literature and also on qualitative and quantitative data gathered during the project. In the course of the project we conducted a brief survey with Ukrainian students and graduates and also several in-depth interviews with other relevant actors involved in the process. The project and the research have rather explorative character since the topic of interest is relatively new. By this report we hope to open up the discussion about the role and the potential of Ukrainian student migration to the Czech Republic.

Basic facts and numbers about Ukrainian migration to the Czech Republic

Geographical, cultural and historical closeness between Ukraine and the Czech Republic are often listed as main explaining factors behind both a long history of Ukrainian migration to the Czech lands and the current situation when Ukrainians represent the largest group of immigrants. The socio-economic situation in Ukraine in recent years in the aftermath of global economic crisis and especially the occupation of Crimea and ongoing war conflict with Russian involvement in Easter Ukraine obviously produces additional push factors for significant number of Ukrainians.

The number of Ukrainian citizens in the Czech Republic has grown rapidly during the last quarter of a century. From less than 10,000 in the early 1990s, the official number of Ukrainian citizens who reside in the Czech Republic today (end of March 2018) has risen to 120,431 people. Ukrainians constitute about 22% of all immigrants and about 40% of immigrants from countries outside the European Union. Today’s number of Ukrainians registered in the Czech Republic is slightly less than it was back in 2008 when the statistics for Ukrainian citizens reached its maximum (CZSO 2018; MoI 2018).

In addition to official number on Ukrainian citizens residing on the territory of the country it could be useful to have a look at the number of immigrants with Czech citizenship. More than 11,000 Ukrainians became Czech citizens within last 25 years: 11,204 acquired citizenships between 1993 and 2017 (CZSO 2018 ). Although earlier studies suggest that many Ukrainians did not apply for Czech citizenship because they did not want to lose their Ukrainian nationality, naturalization trend of Ukrainian immigrants is significantly growing in last years as a result of the new citizenship law introducing the possibility of dual citizenship (Act No. 186/2013 Coll. came into force on the 01.01.2014).

The change in the approach of the Czech state to employment of new coming unqualified immigrants after the economic crisis (namely restricting work permits for unskilled immigrants and regulating visa applications via VisaPoint system) resulted in the slight drop-off and stagnation of Ukrainian immigration to the country. Immigrants who stayed in the country for more than 5 years were entitled to apply for a permanent residence permit. Due to rigid policies towards the new comers obtaining this stable residence status was apparently perceived as a good strategy even by those Ukrainian immigrants who originally did not have plans to settle down (since their chances for repeat migration became rather uncertain). As a result, there was a significant increase in the share of permanent residence permit holders among Ukrainians: in 2000 it was less than one-fifth, while by the end of 2017 it was almost 70% (CZSO 2018).

Ukrainian migration to the Czech Republic is quite young. Almost nine in ten (85%) Ukrainian nationals residing in the Czech Republic are of productive age (between 15 and 59 years of age), while the share of older Ukrainian migrants (aged 60 and above) is negligible (less than 5%) and more than one in ten (11%) migrants officially registered in the country are under 15 (CZSO 2018). Since the 1990s the share of women among Ukrainian migrants has fluctuated around 40%, with a slight increase during the last couple of years. In 2018 the share of women among Ukrainian migrants was almost 47%. More than half of Ukrainians officially registered in the country lives in Prague (43%) and Central Bohemian Region (15%) (MoI 2018).

Contemporary Ukrainian migration to the Czech Republic is characterized by its economic nature. Ukrainian citizens have one of the highest employments to residence ratio among all third country nationals: about 70% of all Ukrainian citizens registered in the country are economically active. According to the estimates by the end of 2016 there were 76,721 economically active Ukrainians, of whom almost one third (29%) were self-employed with the other two thirds (71%) employed under a regular contract.

Most Ukrainian immigrants are employed in the secondary labour market. The most recent detailed statistics available for the end of 2011 shows that about a half (52%) of employed Ukrainians occupied elementary jobs (ISCO 9); while 41% of them were employed in semi-skilled jobs (ISCO 4–8, most often as craft and related trade workers) and only 7% succeeded in securing managerial, professional or other skilled job (ISCO 1–3). When it comes to economic sectors, Ukrainians were mostly employed in construction (44%), manufacturing (21%), wholesale and retail trade, repair of motor vehicles, personal and household goods (8%), and transport, storage and communications (6%). The occupational structure of settled Ukrainians with free access to the labour market (majority of them hold permanent residence permit) was fairly stable between 2004 and 2011 regardless of the economic developments. Though during the same period the employment of Ukrainians regulated by the state (by means of job permits) experienced striking changes: during the economic boom there was rapid growth (especially in elementary occupations), while in just two years after 2009 one could observe a significant decline from almost 49 thousand job permit holders to less than 23 thousand (CZSO 2018).

According to qualified estimates collected by the labour offices by the end of 2016 there were 54,571 Ukrainian citizens employee status, of which 47% were women and 77% had free access to the labour market. (CZSO 2018) Preliminary data for the mid-2017 suggest slightly growing number of employed Ukrainians, especially men and the employee cards holders: by the end of June 2017 69,876 Ukrainians were officially employed in the Czech Republic, of which 43% were women and 69% had free access to the labour market. The recent slightly growing employment trend for Ukrainian immigrants could be associated with success of special governmental projects designed for Ukrainian citizens. First is called Special procedures for highly qualified employees from Ukraine (Project Ukraine). Between its launch in November 2015 and mid-September 2017 this project designed primarily to fasten the visa procedures for Ukrainian immigrants employed in highly qualified professions listed in ISCO 1-3 main groups, had brought only 680 applicants. The second project called Special treatment regime for qualified workers from Ukraine (Regime Ukraine) launched in the end of July 2016 and designed for Ukrainian qualified workers employed in wide range of semi-qualified professions listed in ISCO 4-8 main groups, with a special focus on technical professions in manufacture, services, and also in public sector. Though launched half a year later Regime Ukraine, is much more used by Ukrainian immigrants and their employers: by mid-September 2017 it has 10 170 successful applicants. In a response to a growing demand on the side of the Czech employers, the initial annual quota set for 10,000 applicants was doubled in the end of January 2018.

Though there are no special pro-active projects for unskilled and auxiliary Ukrainian workers, considerable number of Ukrainians comes to the Czech Republic to work in jobs, which are often described as “3Ds” (dirty, dangerous and demanding). According to the data from the Information System on Average Earnings of the MoLSA the average gross monthly wage of Ukrainian employees in the Czech Republic was 22,2 thousand Czech crowns, which is the lowest wage among top 5 employer migrants group and about 23% less than the average wage in the country (CZSO 2018). Although there are no reliable estimates, the irregular component of Ukrainian migration to the Czech Republic is often discussed by researchers and migration experts, especially in connection to the exploitative practices of ethnic intermediates and also recent practices of irregular employment on Polish visas.

As it was mentioned the share of permanent residence permit holders is especially growing since 2008 when the Czech state implemented strict policies (and practices) towards new coming labour migrants. Table 1 illustrates the statistics for the types and the purpose of residence permits for Ukrainian citizens living in the country.

Table 1. Ukrainian citizens in the Czech republic by type of residence permit and purpose of stay in 2011-2017

|

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

|

|

Permanent residence permit |

50 130 |

57 683 |

68 547 |

73 923 |

77 492 |

81 106 |

|

Asylum status |

89 |

93 |

101 |

232 |

405 |

395 |

|

Long-term residence permit (by purpose of the stay) |

68 802 |

54 866 |

36 591 |

30 233 |

28 122 |

28 744 |

|

Humanitarian and other |

– |

– |

– |

1 967 |

2 223 |

2 300 |

|

Family reunification |

– |

– |

– |

6 643 |

6 934 |

7 833 |

|

Study |

– |

– |

– |

1 743 |

2 188 |

2 611 |

|

Employment and business |

– |

– |

– |

19 880 |

16 777 |

16 000 |

|

Total |

119 021 |

112 642 |

105 239 |

104 388 |

106 019 |

110 245 |

|

Source: MoI 2018, CZSO 2018, own calculations |

||||||

A brief look on the data in Table 1 brings two basic findings when it comes to Ukrainian student migration: a) the number of long-term residence permit granted to Ukrainian citizens for the purpose of study is growing, b) the student migration to this country however is still rather rare since the share of Ukrainians with student visa or residence permit is less than 3% among all Ukrainian citizens in the country.

Of course, Ukrainians studying at Czech universities could hold other type of residence permits; for example they could be permanent residence permit holders or they could stay in the country on the basis of family reunification. Therefore in order to estimate the role of student migration of Ukrainians to this country it is more appropriate to consult the statistics provided by Czech universities and collected by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports (MEYS). According to annual data published by MEYS the number of students with Ukrainian citizenship has in fact grown significantly since the beginning of the millennium: from less than 300 in school year 2000/2001 to more than 3 000 in 2017/2018. As of today there are 3 082 Ukrainian students attending Czech universities and 2 662 of them are enrolled in full-time studies of BA and MA programs. Six in ten of all Ukrainian students are women (MEYS 2018; CZSO 2018).

Ukrainians represent about 7% of all foreign students (outnumbered by Slovaks and Russians, who represent 51% and 14% of all foreign students respectively). More than three thirds (77%) of Ukrainians students attend public universities and vast majority of those who study at public universities (95% of all the students at public universities) do not pay for their studies because they are attending Czech language study programmes. Apart from Slovaks (who predominantly not pay for their education), Ukrainian students currently enrolled in Czech universities have the lowest share of the self-payers (4%) among other foreign students. Table 2 provides the statistics of Ukrainian students enrolled at full time studies at top public and private universities in school years 2017/2018.

Table 2. Ukrainian students enrolled in full-time studies at Czech universities in academic year 2017/2018

|

Name of the university |

Bachelor's degree programme |

Master's degree programme |

Follow-up Master's degree programme |

Doctoral |

Total |

|

All public universities |

1500 |

146 |

428 |

143 |

2217 |

|

Including top universities*: |

|||||

|

Charles University, Prague |

137 |

120 |

68 |

51 |

376 |

|

University of Economics, Prague |

208 |

0 |

92 |

4 |

304 |

|

Czech University of Life Sciences, Prague |

245 |

0 |

52 |

2 |

299 |

|

Czech technical university in Prague |

223 |

0 |

49 |

12 |

284 |

|

Brno University of Technology |

124 |

0 |

39 |

8 |

171 |

|

Masaryk University, Brno |

69 |

15 |

33 |

9 |

126 |

|

Mendel University in Brno |

80 |

0 |

8 |

0 |

88 |

|

University of West Bohemia, Pilsen |

58 |

2 |

11 |

2 |

73 |

|

University of Chemistry and Technology, Prague |

45 |

0 |

15 |

10 |

70 |

|

University of South Bohemia in České Budějovice |

43 |

0 |

7 |

12 |

62 |

|

Technical University of Liberec |

42 |

0 |

13 |

1 |

56 |

|

Palacký University Olomouc |

35 |

3 |

11 |

14 |

63 |

|

University of Pardubice |

38 |

0 |

6 |

6 |

50 |

|

All private universities |

448 |

0 |

140 |

2 |

590 |

|

Including top universities*: |

|||||

|

University of Finance and Administration, Prague |

94 |

0 |

57 |

1 |

152 |

|

Metropolitan University Prague |

70 |

0 |

20 |

1 |

91 |

|

The Institute of Hospitality Management in Prague |

52 |

0 |

15 |

0 |

67 |

|

University College of Business, Prague |

33 |

0 |

13 |

0 |

46 |

|

Total |

1948 |

146 |

568 |

145 |

2807 |

|

Source: MEYS 2018, authors calculations * Top private and public universities with more than 50 Ukrainian students are listed here. |

|||||

Unfortunately there is no reliable statistics concerning the field of studies for Ukrainian students in the Czech Republic. CZSO published annual data provided by MEYS concerning university students by groups of fields of education but these data are available only for all foreign students. Thought these data are not detailed and could serve rather for orientation purposes, it is seems that the foreign students are more than Czech students attracted to the health care and pharmaceutical sciences, natural science and also business and administration.

A side from currently enrolled students, MYES also published annual information about Ukrainian graduates. It is impossible to get the accurate estimates for all Ukrainian graduates in the Czech Republic since the detailed data is available only after 2000. According to official records almost three thousand (2 946) Ukrainian citizens graduated from Czech universities between 2001 and 2017 and 67% of those graduates were women (MEYS 2018; CZSO 2018).

Legal and institutional settings related to foreign students

In order to understand the potential of human capital of Ukrainian students in the Czech Republic it is important to begin with the analysis of the institutional settings, especially migration and integration related policies and practices towards foreign students in this country in general. This part of the report summarizes the information gathered by the means of the secondary analysis of available literature and official documents, as well as the qualitative research of the main actors involved in the process. For the purpose of the project we conducted 16 in-depth interviews: with the representatives of 3 relevant ministries (Education, Interior and Labour) and the semi-budgetary organisation Centre for International Cooperation in Education (DZS), Confederation of Employers' and Entrepreneurs' Associations (KZPS), the Institute for Language and Preparatory Studies, Charles University (ILPS CU), and 10 Czech universities. We collected information from 8 biggest public universities in Prague and Brno: Charles University (CU), University of Economics in Prague (VŠE), Czech University of Life Sciences (CULS) Czech Technical University (CTU), University of Chemistry and Technology in Prague (UCT Prague), Masaryk University (MU), Brno University of Technology (BUT) and Mendel University in Brno (MENDELU). The research team also gathered information from two private universities based in the city of Prague: The Institute of Hospitality Management in Prague (IHM) and University of Finance and Administration (VSFS). The selection of the universities for the interviews was based not merely on the size of the university itself but also on the number of Ukrainian students currently enrolled in full-time study programs. By the look on the Table 2 (earlier in the text), in-depth interviews covered majority of top universities with total number of Ukrainian student more than 50.

The analysis in this part of report is focused on recent developments and intended changes in policies and practices related to students migration. Here we discuss the (in)coherence between migration, education, and labour market policies relevant for foreign students in two key areas 1) selection of human capital (focused on promotion strategies, selection of target groups, and admissions policies and practices), 2) enhancement of human capital potential (focused on integration of foreign students and graduates, their transition from education to labour market and plans for the future in hosting country) .

Migration policies and access to education for foreign students

There are three types of higher education institutions in the Czech Republic: public, state and private. According to the Higher Education Act (Act No 111/1998 Coll. as amended) the access to public education is free of charge and the conditions for the admission of foreigners to study in degree programmes are the same as for the Czech students. Cited law prescribes that the obligations resulting from international agreements that are binding on the Czech Republic are to be met. Public universities receive support from the state. There is a special financial contribution for each student enrolled in foreign language programs (regardless the nationality of the students) and total number of students also influence the support.

In order to understand the role of international students it would be useful to shed some light on the recent development in tertiary education in the country. Several studies suggest that the dynamics of quantitative development of higher education in the Czech Republic in the first decade of the century has been very rapid. A steep increase in the number of university students (from 200 thousand in 2001 to almost 400 thousand in 2010) is often criticized as not corresponding to either economic situation in the country or the capability of higher education to adapt to new needs of students and labour market. Mentioned increase could hardly be explained merely by growing number of private schools or the inflow of foreign students as Czech students represented the vast majority (96% in 2001 and 91% in 2010) and their number almost doubled during mentioned period (CZSO 2018).

Koucký and Bartušek (2011) noted that due to demographic change future cohorts of university students will be significantly weaker in the second decade of the century; they warned that even if the number of those supposed to be enrolled in tertiary education will stagnate, their proportion in 2015 will significantly close to 90 % of the corresponding age cohort. Therefore, cited authors (among others) advocated for a significant decrease in the number of students and a need for deep structural and institutional reforms aimed at preventing the inflation of higher education. The total number of students is in fact constantly decreasing since 2010 and in 2017 it dropped slightly under 300 thousand. Migration of Slovak students slowed down a little bit (the number dropped of from about 24 thousand to about 22 thousand) but students from many non-EU countries, especially Russia, Ukraine and Kazakhstan became more interested in studying at Czech universities and their numbers doubled since 2010 (CZS0 2018).

Given the described developments it is clear that Czech universities do have interest in foreign students. Socioeconomic situation in Ukraine makes the financial issue of studies often the crucial for potential Ukrainian students; therefore free of charge access to public education in Czech language is clearly an important pull factor. However, even the students at public universities, who do not pay for their studies, have to think about covering their living costs in the Czech Republic. Given the average salaries in Ukraine and the rate of Ukrainian hryvnya, the financial status of most Ukrainian students is not high. Generally students in the Czech Republic do not receive scholarships for just being enrolled in the studies. The only exemptions are full-time doctoral students, who receive monthly scholarship for a standard period of studies (mostly 3-4 years) regardless of the citizenship. The support for doctoral scholarships is provided to universities by MEYS. The minimum monthly sum for doctoral students in 2017 was about was 7500 Czech crows (a bit less than 300 Euro) thought some universities pay bigger sums from their own budgets. There was a public debate about doctoral scholarships not being able to compete even with a basic salary in the country and in the beginning of 2018 MEYS announced the 50% increase of this scholarship.

Aside from doctoral programs, there are only a few scholarship programs available for Ukrainian students who want to study in the Czech Republic. Few scholarships are available within the framework of the Foreign Development Assistance Programme. These scholarships are awarded to citizens of states receiving foreign development assistance of the Czech Republic and it is provided for a) study in the Bachelor's, Master's and Doctoral study programmes in Czech language (preceded by a one-year Czech language course and preparatory training), and b) a study in follow-up Master's and Doctoral study programmes in English. Government scholarships are provided only for standard length of studies; students receive about 540 Euro monthly, from which they have to cover their transport, living and accommodation cost. The provision of these scholarships is based on the decree of the Czech Government within the frame of a special project of MEYS and MFA; a notice of the scholarship for given year is publicized annually via Czech embassies. Some studies discuss the development impact and the effectiveness of this type scholarships in the light of significantly high share of students who do not finish their studies and high probability of no returns to the country of origin.

Ukrainian students can also apply for scholarships from the International Visegrad Fund and the South Moravian Center for International Mobility; certain opportunities for student mobility of individuals are also possible within Erasmus+ program and some universities offer special scholarships for socially weak and talented students (mostly also available for students from Ukraine).

The interviews we conducted suggest that the representatives of Czech universities seem to realize relative financial weakness of Ukrainian students and they mostly encourage their employment. Interesting examples of targeted humanitarian scholarships were programs announced by Charles University in Prague and Palacky University in Olomouc 2014. The programs provided support to several selected students from Ukraine due to the political situation in the country. In the interview we conducted special scholarships for Ukrainian students in the aftermath of Maidan protests was also mentioned by CULS; the university received about 20 visiting students for winter semester in 2014 at English degree programs.

To sum up, Ukrainian students do not have any special treatment when it comes to scholarships and they are entitled only to a limited number of special scholarships for socially weak students and scholarship for excellent study results provided by different universities. There are also some scholarships and waivers of school fees available at both paid foreign language programs at public universities and at private universities. The offer varies from university to university and there is no complete data available. In general, the research of available scholarship programs suggests that, only a small part of Ukrainian students might receive some financial support from any source.

In order to study in the Czech Republic Ukrainian students have to obtain a visa or a residence permit. There is no special regulation concerning the applicants and normally “third country” nationals who want to come to the Czech Republic for the entrance exam should apply to a short-term visa for stay up to 90 days (visa "C"). A big advantage of Ukrainian students is a visa-free regime, which is in force since June 2017 and applies to citizens of Ukraine who have biometric passports.

Successful applicants enrolled in the accredited study programs at Czech universities can apply for a long-term visa or long-term permit for the purpose of studies. Long-term residence permit for the purpose of studies could be provided not only to students enrolled in accredited study programs at public and private higher education establishments but also to those, who participate in language and professional preparation for studies under an accredited study program organized by a public (not private) higher education establishment, and also for the purpose of not remunerated professional training. Long-term visa for the purpose of "studies" has similar conditions but in addition, it also concerns cases of professional remunerated training carried out during the studies or 5 years after graduating at a higher education establishment. New comer students could also apply for a long term visa for the "other" purpose, which is intended to the foreign national’s education in an unaccredited study program at a public or private higher education establishment or attending language and training courses and programs that do not serve as preparation for studying in a higher education establishment’s accredited study program, as well as education in a school that is accredited or has an accredited study program in the state other than the CR.

An application for a long-term visa is filed in person at a Czech Embassy and the prior registration is needed to file the application. Until recently the registration services were outsourced and all the applicants had to apply for the term via widely criticized Foreign Ministry's on-line system for foreigners' registration called Visapoint. Experts warned that the system is not transparent (quotas were unknown) and often it did not allow registration due to unavailable terms while several commercial structures offered registration for a charge. Visapoint was also very critically evaluated by Czech Ombudsman who (based on observation in Vietnam, Ukraine, and Kazakhstan) claimed that the system is inoperable and found particularly alarming the long-term impossibility to register in order to file an application for a long-term stay for the purpose of family reunification and studies, as these types of stay represent a transposition of EU Directives. The Public Defender of Rights initiated a series of personal meetings with representatives of the MFA and MoI. Since the results of mentioned interventions were unsatisfactory, on the initiative of the Czech Ombudsman the European Commission has launched EC launches action Czech Republic over Visapoint. According to the recent information Visapoint was terminated in the end of October 2017. Today Ukrainian applicants register their term for the visa application via e-mail.

Meanwhile as a reaction to the critics of Visapoint and the growing demand for foreign students from universities a special project Regime student was launched in May 2017. Regime student is a result of cooperation between the MoI, MEYS and MFA and it is supposed to ease a process of applying for student visa for third-country nationals. Students admitted to Czech universities included in the project no longer have to apply for visa through Visapoint but can ask for the appointment directly at the embassy, which in its turn has to try arranging the appointment with the applicant so that the starting date of the residence permit and the beginning of his studies could collide. The participation of the students in the project is however limited by strict quotas and available only to students from selected countries. According to official information the annual quota for Ukraine in 2018 is rather generous: monthly quota for consular department in Kyiv is 36 and for Lvov it is 13 student applicants. Given the cancelation of visa point the effectiveness of this regime for Ukrainian students is questionable and participation in it is not connected with other bonuses.

According to the interviewed representatives of MoI student visa applications nowadays have over 90% success rate, which is one of the highest compared to other visa applications. Yet it is not the success rate but the complicated process itself and the delays what is often criticized. There is no hard data or in-depth research on visa problems for newly enrolled students but apparently the process is not going smoothly even for this group of relatively not problematic immigrants. Administrative complications and delays in issuing student visas were acknowledged by Horký et al. (2011) even in case of students awarded with governmental scholarships and it is also discussed in many other wider studies dedicated to Ukrainian migration to the Czech Republic. In the interviews we conducted several university representatives and MEYS pointed out that strict visa policy reduces number of incoming foreign students and academic staff.

According to Employment Act (No. 435/2004) students enrolled in full-time studies at accredited study programs at Czech universities and also graduates from these programs have free access to the labour market. Free access means that these students and graduates have same rights as Czech citizens, i.e. they do not have to obtain any special work permit and can sign all kinds of working agreements without any limitations concerning working hours. Current students can also work during the holidays within academic year they are enrolled into. Free access to labour market does not apply to those who study in uncredited programs and have permit for “other purpose”.

In order to work after the graduation non-EU citizens have to have valid residence permit. Student residence permit is valid only till the end of the studies and if foreign students want to stay in the Czech Republic after graduation, they have to prove their purpose of stay in order to change the type (purpose) of their permit. They do have free access to the labour market but in order to stay and work in the country after graduation they have to find a job and to arrange all necessary documents before the end of the studies so that they can apply for an Employee card. Employee card is a new type of single permit (dual document) authorizing foreigners to both stay (longer than 3 months) and work on the territory of the Czech Republic. It also exists in the form of a non-dual document (basically only a residence permit) for those who have free access to the labour market and it could be issued for maximum 2 years (or shorter period mentioned in the contract) with possibility of repeated extension of validity. Graduates, who want to start their own business, can also apply for a trade licence and entrepreneurial stay permit. Again, trade licence had to be arranged in advance (during the studies) and application for a change of purpose of stay should be done before the end of student residence permit.

An important disadvantage of non-EU students is rather limited access to health care. All foreigners staying in the Czech Republic on a long-term basis are legally obliged to participate in health insurance immediately after entering the country and throughout their stay. Foreigners may meet this obligatory requirement via general or commercial health insurance. If foreign students are not employed in the Czech Republic they don't have access to public health care and they have to buy commercial health insurance, which has a lot of limitations and exceptions, as for example, treatment of chronic diseases, dental care (if it's not an emergency) and preventive health checks. Students represent potentially less risky group of so called “healthy migrants” because they are relatively young and mostly not at risk of dangerous working conditions. Nevertheless, given the overall socio-economic status of many Ukrainian students who could hardly afford paying for a costly medical treatment, the full access to medical care covered by public health insurance seems to be an important precondition for successful integration. Lack of access to public health insurance for considerable part of immigrants and insufficient guarantee of legal entitlement to health care is often criticized by NGOs, researchers and experts as one of the most urgent problem of Czech health policy in relation to immigrants.

Recruitment and promotion strategies

Internationalization of tertiary education is set as one the priorities in Czech Long-term strategy for university education for the period for 2011-2015 and it is further elaborated and specified in current strategic document for 2016-2020 and relevant Action plans. Attracting foreign students to Czech universities is a part of internationalization strategy, but clearly, it is not the only goal of it. Long term strategy for 2016-2020 mentioned following subtasks among others related to the priority of internationalization: to reflect internationalization in the financial support provided to public universities, to support mobility of students and academic staff, to support joint study programmes, to create a joint portal for international representation Czech universities. The strategic document also recommends Czech universities to a) improve integration of foreign students and academic staff and to use their potential more effectively, and b) to focus international cooperation on priority region based on evaluation of previous cooperation.

In order to perform tasks involved with ensuring educational, training and other relations with foreign countries MEYS established a semi-budgetary organisation The Centre for International Cooperation in Education (DZS). This organisation is carrying a number of activities relating to the promotion of education. DZS provides services to a wide range of relevant actors, like individuals, students, teachers and directors of all types of schools, other professionals, and organisations involved in education as well as local authorities and MEYS.

None of the mentioned above strategic documents on education policy sets priorities towards certain countries or types of students. In the interviews we conducted both, MEYS and DZS mentioned the importance of bottom-up approach. The demand for foreign students (as well as the priorities towards certain countries or students in given study programs) is determined by universities themselves based on their experience with current students and cooperation with universities abroad. When it comes to the recruitment and selection strategies implied by universities, our research suggests that most Czech universities don’t have special recruitment strategies for Ukrainian students. Usually a standard recruitment process is applied for enticing foreign students regardless of the country of origin. Among those general promotion practices are international student fairs abroad and in the Czech Republic (Gaudeamus exhibition was explicitly mentioned by VSFS), online and social media promotion and some targeted advertisement.

The majority of contacted universities is more concentrated on promotion of English degree programs. This is usually done through general practices of Marketing and PR office (BUT) or Admission and Marketing office (VŠE) or through PR office and office for International Relations (CTU). There are two special web page projects promoting university education in the Czech Republic. Prague universities, such as CU, VŠE, UCT Prague, CTU, CULS, UMPRUM and AMU promoting the possibility to study at their universities in a frame of university consortium and through studyinprague.cz web page in English language. This project is financed by the Ministry of Education. Another web page, which promotes the possibility to get university degree in the Czech Republic and involves information about universities in the whole country, not only in Prague is studyin.cz webpage, which is also in English. This web page is operated by the Centre for International Cooperation in Education (DZS).

In terms of language strategy, all contacted universities have their web page not only in Czech, but also in English. Only UCT Prague and VSFS have also Russian version of their web pages. MU once had a brochure in Russian for some bigger educational fare and Bachelor degree study program of Ukrainian Studies at the Faculty of Arts also had a leaflet in Ukrainian for potential students. Given the language closeness, it is logical that the majority of Ukrainian students at public universities attend Czech language programs. The language barrier is clearly not that challenging for Ukrainian immigrants. In fact, previous studies suggest that Ukrainians in the Czech Republic are mostly self-taught. However, those who plan to apply to Czech universities could attend different language and preparatory courses, both in Ukraine and in the Czech Republic. Some universities (for example UCT Prague, VSFS, VŠE, CU) offer self-paid 1 or 2 semesters Czech language classes. In some cases these language classes are combined with preparatory courses called “zero academic year”. During this year foreign students often have orientation lectures for given university and combination of some degree courses. By attending the “zero academic year” potential student is not only preparing for the entrance exams but also receives certain benefits, like for example recognition of courses (credits) or even acceptance to the second academic year. These preparatory courses are targeting not only potential foreign students but also unsuccessful applicants.

As it was already mentioned, some universities promote their study programmes directly in Ukraine and recruit students there. Cooperation with partner universities in Ukraine was mentioned as one of the ways how to outreach to potential foreign students. This promotion strategy could be especially effective for a follow-up master or doctoral study programmes, when the Czech university selects and attracts outstanding graduates from the partner universities abroad. This recruitment strategy was especially emphasized by CULS as a means of getting “preselected, good quality” applicants. Some Czech universities have singed bilateral agreements with partner universities in Ukraine. For example CU representative mentioned 4 bilateral agreements with Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, Ivan Franko National University of Lviv, Uzhhorod National University and Odessa I. I. Mechnikov National University. Bilateral agreements allow Ukrainian students to participate in student exchange. Cooperation with local high schools in Ukraine and short study visits were also mentioned as the promotion strategy by MENDELU, which has accepted up to 50 best students from a Kharkiv high school, who have an opportunity to visit Brno and MENDELU as a prize for their study achievements.

Another important means of promotion is participation on international education exhibition in Ukraine. The Czech delegation to the education fair in Kyiv in March 2018 consists of representatives of Centre for International Cooperation in Education (project Study in the Czech Republic) and 11 public and 2 private universities. In the interviews we conducted the representatives of 5 universities explicitly mentioned participation in Kiev’s international education fair as a method of propagation and recruitment.

Czech Centre in Kyiv is an important player for promotion of Czech university education in Ukraine. Czech Centres are a contributory organisation of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Czech Republic and their mission is to promote the Czech Republic abroad. Apart from assistance to relevant partners during the educational fairs in Ukraine, Czech Centre in Kyiv provides counselling to those who want to know about education in the Czech Republic and they even assist some potential students in selecting appropriate universities. The web pages of Kyiv Centre also publish successful stories of enrolled Ukrainian students sharing their experience and advices about applying and studying at Czech universities. However, the most important contribution of the Czech Centre is connected with its activities within wide network of Czech language courses organized in 9 Ukrainian cities (including important university cities Kyiv, Lviv, Kharkiv and Dnipro).

As it was mentioned, most of the Czech universities do not have any special promotion strategy for Ukraine and they often employ broader strategy towards ex-USSR countries, as a region with significant Russian speaking population (including Russia, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan etc.). This was mentioned in many interviews; representative of VSFS pointed out that Ukrainian educational market is generally treated as a part Russian speaking educational market. VSFS representative mentioned the importance of cooperation with educational and travel agencies abroad (not only in Ukraine). These are local agencies in country of students’ origin, which promote education abroad, recruit students and help them with administrative and visa processes. These agencies are very often oriented on Czech Republic and have all needed know how for the whole process of sending students to study abroad.

In fact, the global competition and internalization of higher education has led to a rise in the number of international students and education abroad became a big business also in the Czech context. Universities, language schools, and other educational institutions work to entice international students and Czech Republic is not an exception. As free of charge access to university education requires the knowledge of Czech language, the important gateway for foreign students is through Czech language preparatory courses provided by different actors: the Czech centres aboard, the Czech universities themselves and also private language schools in Ukraine and in the Czech Republic. There is a wide range language courses (of different intensity and duration) available in the Czech Republic. And obvious the Czech language schools are those who are financially interested in the inflow of foreign students at Czech degree programs at universities. At the same time, in the interviews we conducted universities acknowledged that they are most interested in students in English degree programs (as this means money from tuitions and subsidy from the government). And while universities put more effort in marketing activities which are targeted to English speaking students, language schools usually are more oriented on students’ groups, who are more linguistically close to the Czech Republic, as for example students from so called Slav group, including Ukrainian students.

There are private Czech language schools, which offer Czech language classes often in cooperation with some universities and faculties. As for example UniPrep, which is a private school cooperating with Faculty of Humanities, CU in Prague and offering some courses at the faculty during the preparatory language courses. The Prague Education Centre doesn’t offer the possibility to take some courses at particular university or faculty, but in Brno it has Czech language classes in BUT. The preparatory business is evidently successful enough that some of the private schools offer the financial guarantee of being accepted to Czech university. The payback as a guarantee is offered to those who attend their courses (and sometimes pay extra) and there is even a list of educational programs/majors (mostly with a shortage of students) at public universities for given year. This striking example of a marketing tool used for enticing international students reflects not only the success of the migration business but also the nature of structural opportunities in the Czech context. The role of private preparatory schools seems to be important, though it seems that their business is targeting wealthy students mostly from Russia and Kazakhstan. In any case, more in-depth research of the practices of these private schools and the interconnections with Czech universities would be desirable to get the full understanding of the situation.

Moreover, many universities, as it was already mentioned, offer Czech language preparatory courses by their self. These courses were explicitly mentioned by the representatives of VŠE and CTU in cooperation with The International Union of Youth and The Institute for Language and Preparatory Studies (further ILPS) at CU. It’s possible to say that ILPS one of the biggest player on that market, as it offers language preparatory courses not only in different places in Prague but also in Podebrady, Marianske Lazne and Liberec. Among the main activities of ILPS belong preparatory courses for university studies, including preparation of students who study in the CR in the framework of governmental scholarships. The courses include intensive Czech language courses and courses that prepare for entrance examinations at Czech universities (by different field of studies). Besides that, ILPS offers preparatory courses for studies at Czech universities in English, non-intensive Czech language courses, summer schools of Czech language, Czech language courses for doctors, courses for foreigners who want to pass the test necessary to obtain Czech citizenship, preparation for Czech language exams, individual courses, foreign language courses.

In addition, ILPS helps with recognition of foreign education and provides accommodation. Besides having a representative in Ukraine who helps prospective students with application process (the same services are provided for Russian students in Moscow), there are no special services for Ukrainians. ILPS advertises its services on its webpages available in English, Russian and Czech and cooperates with firms in Ukraine that assist Ukrainian students who intend to study abroad.

A private company “Home in Prague” is the most important contractor of ILPS that supplies the highest number of students. They focus on countries where Russian is spoken and understood – besides Russia, this means Ukraine, Kazakhstan etc. This year, out of 667 students in preparatory courses 276 were recruited by the firms. The firms receive for each recruited student a provision. They run campaigns at Ukrainian high schools presenting ILPS services and providing introduction to the Czech higher education system. ILPS also cooperated with Czech embassy. Czech language students at the Czech Center often take preparatory courses at ILPS. ILPS has its representative in Ukraine, who helps prospective students with the application process and represents ILPS at education fairs there. According to interviewed representatives ILPS is more oriented on middle class students and current socio-economic situation in Ukraine resulted in a slight drop off in the number of students. At the same time they noted the importance of migration regulations and stated that cancelation of Visapoint was a relief and it coincided with rise in number of Ukrainian students.

ILPS visits the regularly meetings for providers of education, organized by the Ministry of Interior, where it informs about current policies and changes in legislature. Although ILPS is influenced by them, it does not question migration policies of the state. It cooperates with the Ministry of Interior and tests applicants for the permanent residency proficiency in Czech and serves as an arbiter if doubts on the applicants’ proficiency in Czech language arise. ILPS representative mentioned unsuccessful attempt to cooperate with the Ministry of Health on preparation of courses for foreign health personnel that prepares for exercising their profession in CR and needs to recognize their qualification in CR.

In general, ILPSs representative expressed his dissatisfaction with current state of affairs, as there is lack of cooperation between respective actors involved in recruiting foreign students and that hinders ILPS work. He implored the project to do something about it. For example, he mentioned requirements for the entrance examinations that are not unified. Some schools require B1 level, others B2 level. Among faculties of the same field the requirements are not as well unified. ILPS also complained about the lack of interest from the side of Ministry of Health to cooperate on the courses for foreign health professional etc. Such cooperation would be very useful, as the popularity of preparatory courses for studies of medicine and technical subjects have risen recently and overshadowed popularity of preparatory courses for humanities and economics. According to ILPS representative, it is because students found out that it is much harder to succeed as a foreigner in humanities than in technical subjects. ILPS representative believes that employment opportunities are much higher in medicine and technical subjects but there is no data to confirm this trend among Ukrainian graduates.

According to ILPS representative, Ukrainians are usually well fitted to study in CR. They are able to learn language quickly and there are no crucial differences in syllabi at Ukrainian high schools and Czech high schools, especially in technical subjects. Therefore, Ukrainian students prepare easily for the entrance examinations at Czech universities. However, it is hard to assess how successful students are at the entrance examinations and in the run of their studies. As Universities are forbidden to provide information to the third parties ILPS depends on the information provided by the students themselves. Unfortunately, the return rate of questionnaires is low, because ILPS usually has students’ addresses at Ukraine as a contact addresses and it’s hard to reach them there, as many of them no longer live at Ukraine.

Policies coherence

Coherence between migration and education policies seems to be a challenging issue in the Czech context. Migration regulations clearly pose barriers to efforts for internationalization, which is one of the priorities of education policies. Representatives of MEYS, DZS, and several universities acknowledged that due to complicated and long visa procedures in the Czech Republic foreign students are often incapable to start their study program in time, i.e. they receive visa after the start of the academic year. Ukraine is however considered to be less problematic. The obstacles caused by Visa point were partly solved by introducing Regime Student, which was kind of a compromise between keeping the strict regulations on the entrance to the Czech Republic for Ukrainian citizens (especially labour migrants) and solving the problem of too strict visa procedures for Ukrainian students, as demanded and third popular source country (after Slovakia and Russia).

There seems to be a certain clash of interests between the MEYS on one side and MoI on the other side. The priority of MoI is securitization; while the priority of the MEYS is internationalization of the higher education preconditioned by liberal policies concerning entrance of foreign students. In the interview, representatives of MoI pointed out that some young immigrants misuse student visa as they change university after just one year or they do not attend classes because the main purpose of their visit is rather economic activities than studies. MoI could not estimate the extent of such practices but they clearly problematize the issue for a while, since similar concern could be found in a brochure dated three years ago. Representatives of MEYS however believed that Ukraine is not one of the countries with massive abuse of student visa.

In fact, migration policies have a twofold effect on recruitment of foreign students and if the regulations towards given country are too strict, both universities and students lose their interest. Universities cannot afford losing many prospective students who were already admitted and after some unsuccessful attempts they simply reorient towards other countries. Students also calculate their potential risks and efforts and if it is too hard to obtain visa to a given country, they look for more accessible destinations.

The report by the Education policy centre at Charles university suggests that graduates in the Czech Republic has one of the highest rate of employment of students before graduation. According to the results the Czech waves of comparative European research project REFLEX focused on higher education graduates the average length of transition from education to first job in the Czech context was shortening between 2006 and 2013 from slightly more than 5 months to slightly less than 3 months. Almost one half (48%) of more than 27 thousand of Czech graduates included in the survey of 2013 claimed that they were already working before the graduation; only 2% of them never had job after the graduation while the rest reported to start working either up to three months after the end of the studies (28%) or in a longer period of time (21%). The study also suggests slight decrease of graduates who are employed exclusively in the field of their studies and growing importance of those working in related fields (self-reported by the graduates). The share of those who reported to work in completely unrelated field (or in jobs without any special requirement concerning the field of studies) was relatively high among those who studied social sciences and humanities, culture and arts and also agriculture, forestry and veterinary; the highest rate of perfect match between the field of work and studies was reported by graduates with degree in medicine and law, while graduates with degrees in economics, natural sciences and technical study programmes were mostly employed in other related fields. At the same time graduates with master and doctoral degree are more successful in matching theirs job with education.

The problem of incoherence between educational system and labour market needs was discussed in the interview with representatives of MEYS and DZS, who noted that the shortage in domestic labour in particular sectors in fact do not influence promotional or recruitment campaigns. Strategies in a sector of higher education are long-term, whereas shortages in the labour market are usually short-term problems that cannot be solved merely by changes in the sector of education. This of cause does not mean that labour market needs do not influence higher education at all just that this connection is not straightforward. Contacted MEYS experts acknowledged some demands to focus more on skills and capability to solve problems than on encyclopaedic knowledge; however, mentioned claims are embedded in a broader concept and they are not elaborated into the demand for particular sectors or degree specializations. It was mentioned that, in comparison to other European countries in CR business is not well connected with public institutions of higher education and this lack of connection is seen as a weakness. There have been a few attempts to connect business and public higher education. Practical trainings done within the Erasmus+ programme are one of them. For example, students of medicine can go on exchange practical trainings in hospitals. Some technical faculties also develop applied research in which they engage doctoral students. Nevertheless, undergraduate and postgraduate students are not usually involved in this kind of programs and none of these activities significantly influence promotional campaigns.

Some attempts to connect business and education are done by private institutions. An interesting and in the Czech context unique example of practical overlap between industry and education could be Skoda Auto University (SAVS), a young private university founded by the automobile company. According to information obtained from SAVS, internationalization is also one of their priorities. They offer bachelor’s and follow-on master’s degree programmes (both in full-time and part-time) and claim to regularly update their study programs to meet the requirements of today’s professions. At the moment there are only 28 Ukrainian students at SAVS, which is about 8% of foreign students and 4% of all the students. SAVS has English and Russian versions of the website and they also cooperate with “agent companies” that contact prospective students. SAVS follows the carriers of their graduates and has practical internship as an obligatory part of the bachelor’s study programme.

Last but not least, mentioned incoherence between education and integration policies lies in the problem of enhancing and utilizing the human capital of foreign graduates. Clearly, transition from education to labour market is a challenge for all the graduates, but Ukrainian students (as well as students from other non-EU countries) might experience even bigger problems due to their uncertain legal status. Dual vulnerability of the status of foreign graduates is given by the fact that they are mostly not entitled to unemployment benefits not just in case they did not work before (at least six months of employment within last three years is required) but also due to their legal status (unless they have permanent residence permit in the country). MLSA does have statistics on unemployed Ukrainian citizens registered at labour offices but these record do not provide the information on number of unemployed foreigner graduates (according to the interview with MLSA in case of foreigners this information is not recorded).

Czech Republic does not seem to articulate any special interest in keeping foreign graduates in the country. Apart from free access to labour market, the advantage of the studying experience is recognized when it comes to requirements concerning language tests for permanent residence permit and citizenship application as graduates from study programmes in Czech do not have to pass these compulsory tests. Nevertheless, a significant disadvantage of Ukrainian graduates (even comparing to low-skilled labour migrants) is the fact that they cannot apply for a permanent residence permit even after 5 years of studying in the country. Immigrants who stay on the territory of the Czech Republic for at least 5 years are normally entitled to apply for this stable residence permit status associated with many advantages, including the access to public health insurance, unemployment and social benefits. However, the duration of studies for the purpose of permanent residence permit is calculated only with 0.5 coefficient. Therefore, even graduates with degree in a very demanded field, who spent almost 10 years in the Czech Republic on student permit have absolutely no guarantee of stay after the graduation and in case they fail to change the purpose of their stay immediately after graduation they have to leave and to reapply for another type of residence permit abroad and therefore they lose their “continuous residence record” for the purpose of future permanent residence permit application. These regulations go against the assumption that skilled foreign graduates with Czech diploma and knowledge of the language are one of the most appropriate and easy target groups of any integrational policies. The amendment to Alien law, which is still under the preparation, plan to introduce some kind of transition period, enabling foreign graduates to remain in the country for 9 months after the graduation in order to find a job. This would definitively improve the situation of foreign graduates who decided to stay in the country, yet the discussion of possibility to eliminate described above disadvantages of graduates applying for permanent residence permit still appears very desirable.

Ukrainians students and graduates – numbers, profile, plans

This part of the report analyses the data form the on-line survey of Ukrainian students and graduates in the Czech Republic, which lasted for about 7 weeks between March 29 and May 16. The details of the survey process and its promotion are described in the methodological annex to this report. As a result of the survey we collected the data from 307 respondents, including 48 graduates and 259 current students from Ukraine. Graduates and students answered to slightly different set of questions, therefore these two groups were analysed mostly separately. While reading the results and the interpretations further in this report, one should keep in mind a small number of graduates involved in the survey. Although we provide some percentages not only for students but also for graduates here, those figures should be interpreted with a great caution since they have very low statistical power. The results for graduates should rather serve for orientation purposes also because the process of recruitment for the survey, which was more oriented on current students (particularly targeting Czech universities).

The profile of Ukrainian students and graduates in Czech Republic

The proportion of men and women among students and graduates is very alike with a domination of women (69% among students and 65% graduates); though, logically, current students in the survey are significantly younger (more than 75% of them are younger than 24; while the majority of graduates are older than 26). Statistics for students attending Czech universities for the past 10 years also reflect the predomination of women among Ukrainian students; though the share of them in official records is somewhat lower (stable about 60%). Table 3 provides the comparison of the age and gender composition of survey respondents and Ukrainian students and graduates in official records.

|

Students |

Graduates |

|||

|

Survey |

Statistics* |

Survey** |

Statistics*** |

|

|

Gender |

||||

|

Male |

31% |

40% |

35% |

33% |

|

Female |

69% |

60% |

65% |

67% |

|

Age |

||||

|

16-17 years |

1% |

1% |

0% |

0% |

|

18-20 years |

34% |

36% |

0% |

4% |

|

21-23 years |

41% |

37% |

6% |

34% |

|

24-26 years |

15% |

15% |

25% |

34% |

|

27-32 years |

8% |

9% |

35% |

23% |

|

More than 32 years |

2% |

2% |

33% |

6% |

|

Source: Ukrainian Students Migration to Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, the Slovak Republic: human capital perspectives, 2018 (N=307); MYES 2017; authors calculations *Statistics for Ukrainian students is valid for the school year 2017/2018. **Due to the small number of graduates in the survey (48 respondents) one should interpret the percentages with caution. ***Statistics for graduates are valid for 2001-2017; the age at graduation is mentioned here. |

||||

As it was already mentioned, it is impossible to get the accurate estimates of the age and gender composition of all Ukrainian graduates since the detailed data is available only after 2000. The aggregated statistics published annually by MEYS bring information also about the age of graduates for respective years. Table 3 illustrates the number of graduates in age groups but this aggregated statistics provide data for the age at graduation and it should serve rather for orientation purposes. Direct comparison with the survey sample could be even misleading since graduates are getting older and some of them leave the country (they are harder to target by the survey).

When it comes to the coverage of Czech universities, majority of students and graduates recruited for the survey came from five larger public universities all around the country: Czech University of Life Sciences in Prague (23% of the sample), Masaryk University in Brno (20%), Charles University in Prague (17%), Brno University of Technology (8%), and Jan Evangelista Purkyne University in Ústí nad Labem (5%). Table 4 illustrates the number of students and graduates in the sample by university.

|

Table 4. Universities covered by the survey |

||

|

Students |

Graduates |

|

|

Czech University of Life Sciences (CULS) |

68 |

1 |

|

Masaryk University (MU) |

53 |

7 |

|

Charles University (CU) |

30 |

21 |

|

Brno University of Technology (BUT) |

23 |

0 |

|

Jan Evangelista Purkyne University (UJEP) |

15 |

1 |

|

Technical University of Ostrava (VSB-TUO) |

12 |

2 |

|

University of Economics in Prague (VŠE) |

6 |

8 |

|

Anglo-American University (AAU) |

10 |

0 |

|

Czech Technical University (CTU) |

6 |

3 |

|

Metropolitan University Prague (MUP) |

4 |

1 |

|

Technical University of Liberec (TUL) |

3 |

1 |

|

Palacky University Olomouc (UPOL) |

4 |

0 |

|

University of West Bohemia (UWB) |

3 |

1 |

|

Tomas Bata University (TBU) |

3 |

0 |

|

Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague (UMPRUM) |

2 |

0 |

|

The Institute of Hospitality Management (IHM) |

2 |

0 |

|

University of Finance and Administration (VSFS) |

2 |

0 |

|

Mendel University in Brno (MENDELU) |

2 |

0 |

|

University of Chemistry and Technology in Prague (UCT Prague) |

2 |

0 |

|

University College of International and Public Relations Prague (VSMVV) |

1 |

0 |

|

University of Veterinary and Pharmaceutical Sciences Brno (UVPS Brno) |

1 |

0 |

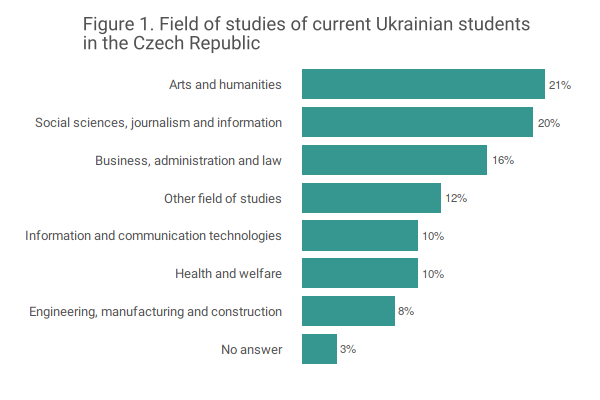

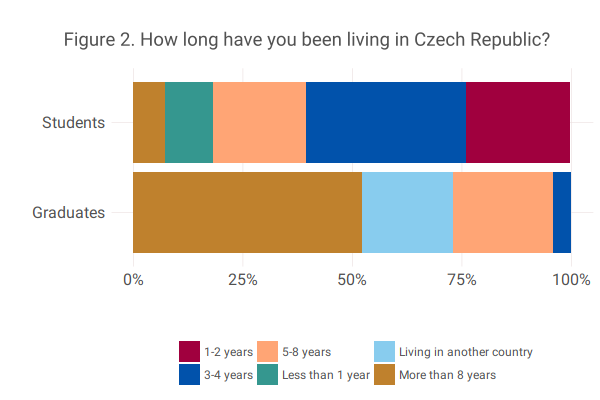

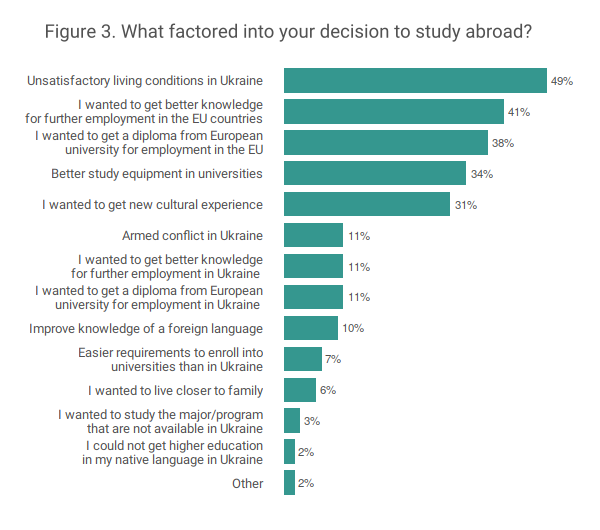

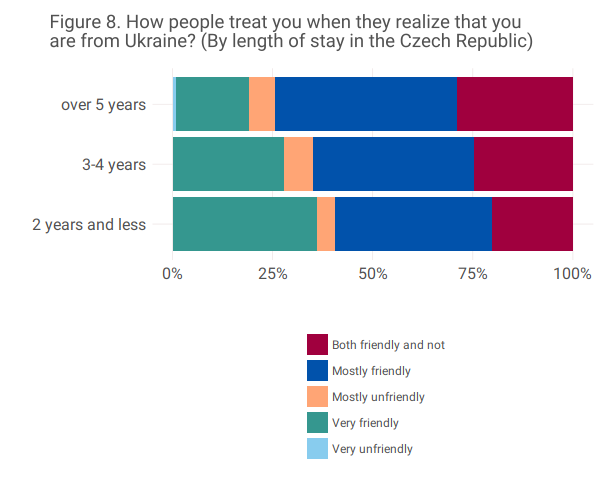

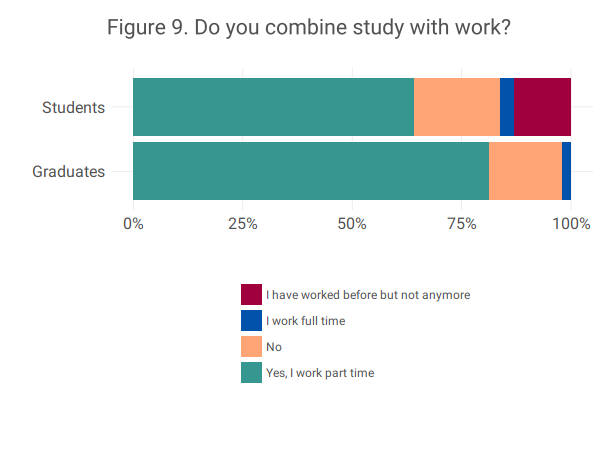

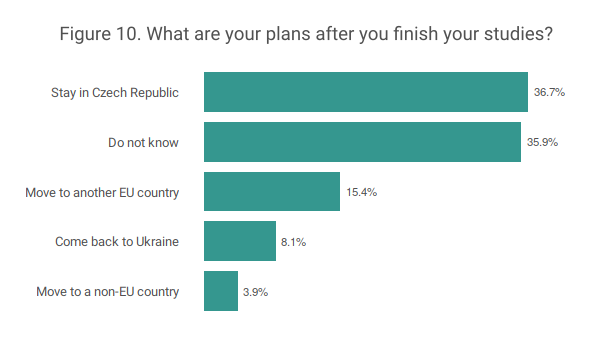

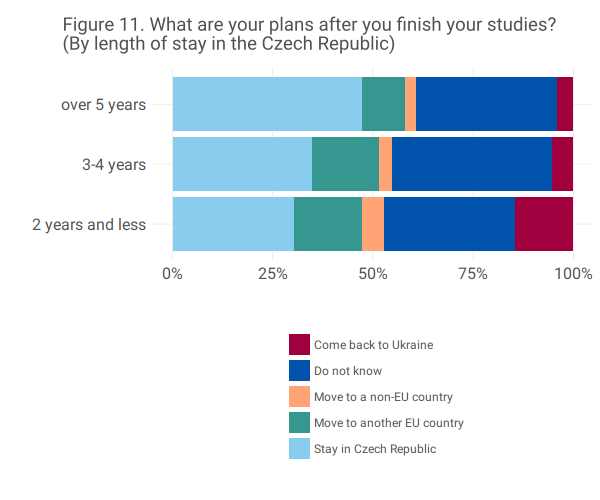

|