This report was produced under the Ukrainian Think Tank Development Initiative (TTDI), which is implemented by the International Renaissance Foundation (IRF) in partnership with the Open Society Initiative for Europe (OSIFE). TTDI is funded by the Embassy of Sweden in Ukraine. The views and interpretations expressed in this report are the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Sweden, IRF and OSIFE.

Authors:

Mariia Kudelia – education policy analyst at CEDOS think tank

Ihor Samokhin – education policy analyst at CEDOS think tank

Review:

Olga Shumylo-Tapiola

Iryna Kohut

Until recently, Ukraine’s education was managed by state administrators who were far from local communities. This centralized administration had a negative impact on the quality and accessibility of secondary education, especially in villages and small towns. With the power to manage education together with the ability to allocate funds now transferred to communities, these communities have the opportunity to address their needs at the local level, which offers hope for improved education for children. However, the jury is still out on whether this change will bear fruit and if local communities will be able to manage their new responsibilities.

From an Old Education System to the “New Ukrainian School”

Old education system: No access to high quality education

Independent Ukraine inherited an extensive network of secondary education institutions — comprised of 21,900 schools — from the Soviet Union, which continued to expand after 1991. In just four years, there were over 22,300 schools with nearly 7 million students. The number of schools eventually decreased, but the population was shrinking faster. In 2013, there were 4 million children enrolled in 19,300 schools. However, as schools in small towns and villages lost many students due to the massive migration of families to large cities and abroad, the number of students in large cities exceeded the number of available seats, creating demand for new institutions. In 2013, the average number of students in urban schools was 427, whereas in rural schools the average was only 107 children. In the most depopulated villages, schools were almost empty, with some classes not having even five students.

Independence did not improve the quality of education in Ukraine: neither the curriculum nor the teaching methods were updated to meet the needs of contemporary society. The situation was even worse in small cities and villages, as children from schools there showed worse results in independent testing. These poor results could be explained both by the socioeconomic status of rural residents and poorer quality of education in rural schools. Villages had a shortage of young professionals, including teachers, and as a result it was difficult for rural schools to fill their teachers’ vacancies. In many cases, teachers were assigned to teach subjects out of their expertise. Rural schools often lacked the necessary equipment and supplies for practical and laboratory work; there was often a shortage of textbooks.

The “New Ukrainian School”: A hope for better education

By the time the Revolution of Dignity took place in 2014, the education situation required drastic changes. The government announced comprehensive secondary school reform in 2014. However, the reform was articulated in the new Law on Education adopted by the Ukrainian parliament only in September 2017. The reform aims at implementing the concept of the “New Ukrainian School” by changing the structure of secondary education and introducing a child-oriented approach, and most importantly, shifting the power of education management and resource allocation from the central government to the communities.

As during the Soviet period, independent Ukraine did not divide schools into elementary and high schools: students attended one school for 9 or 11 years. The “New Ukrainian School” concept plans to increase the number of years at school from 11 to 12 to provide students with more time to prepare for adulthood. It will also be the first step to making the Ukrainian education system more compatible with European systems. Schools themselves would be divided into primary education (4 years), basic secondary education (5 years), and profession-oriented secondary education (3 years), which will replace 10th and 11th grades. The latter would offer two dimensions: academic education for those who may wish to continue with a university education and professional training for those who choose not to.

The main focus of the “New Ukrainian School” would be children’s development by building the competencies needed for self-fulfillment rather than academic records. A competency approach would be introduced for all students starting from the first grade. The key competencies include but are not limited to information and communication technology, environmental awareness, lifelong learning skills, and participation in community life. The teaching strategy would be modified and tailored based on individual abilities and interests of students. School students would have the opportunity to choose subjects and their level of difficulty, which was earlier centrally planned and imposed on Ukrainian school students.

The problems with the shortage of students in small cities and villages would be tackled by optimizing the school network. Reducing the number of schools in rural areas by combining schools and using buses to transport children to their nearest schools was considered a viable solution. This process would allow schools to save money on operations and maintenance of underused school buildings and allocate resources for the modernization of remaining school buildings.

Toward Better Schools: Education and Decentralization Hand-in-Hand

The reforms of government decentralization and education were started at approximately the same time. By moving forward hand-in-hand, the two reinforced each other. Education reform aimed at changing the substance of schooling, whereas decentralization sought to improve governance.

Transfer of Power: What’s on paper?

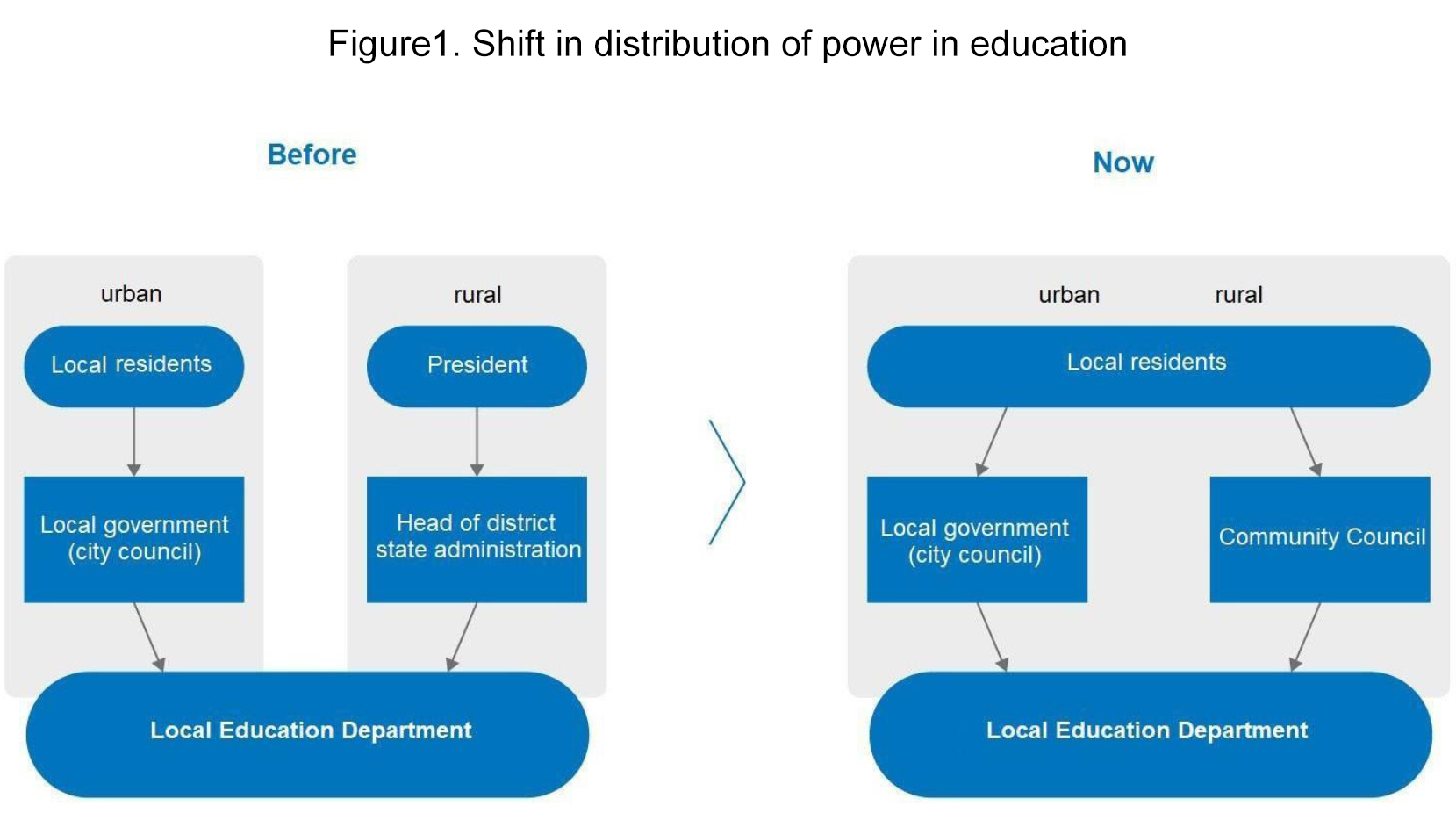

In independent Ukraine, a dual system of local government was formed: all regions and districts had both an elected authority (a local council) and the head of regional and/or district state administration appointed by the president. A local education department belonged to the state administration, thus under presidential control. Only in the cities (except the smallest ones) was the education department subordinated to a democratically elected city council. In rural schools, a district council had very little impact on education: the district state administration appointed school principals and other staff members, and it also controlled the distribution of funds. A department of education within a district state administration was only partially regulated by the Ministry of Education.

The Law on Voluntary Amalgamation of Territorial Communities (ATCs) — adopted in 2015 as part of the decentralization process — envisaged the creation of ATCs on the basis of villages and towns in Ukraine’s regions. The idea was to shift power from the center to the community level, including in the sphere of education.

The ATC councils were given power similar to that of the district councils under the central government. The ATC councils were made responsible for the implementation of national education policy, planning and development of the school network, establishment of school attendance areas, arranging and covering the cost of students’ transportation to schools, and disclosure of all revenues and expenses. They were given the right to decide the optimal number of schools for their communities. An ATC was empowered to set up its own education department and methodology service, and given the right to to decide the number of staff members and determine its scope of responsibilities.

Transfer of financial management: What’s on paper?

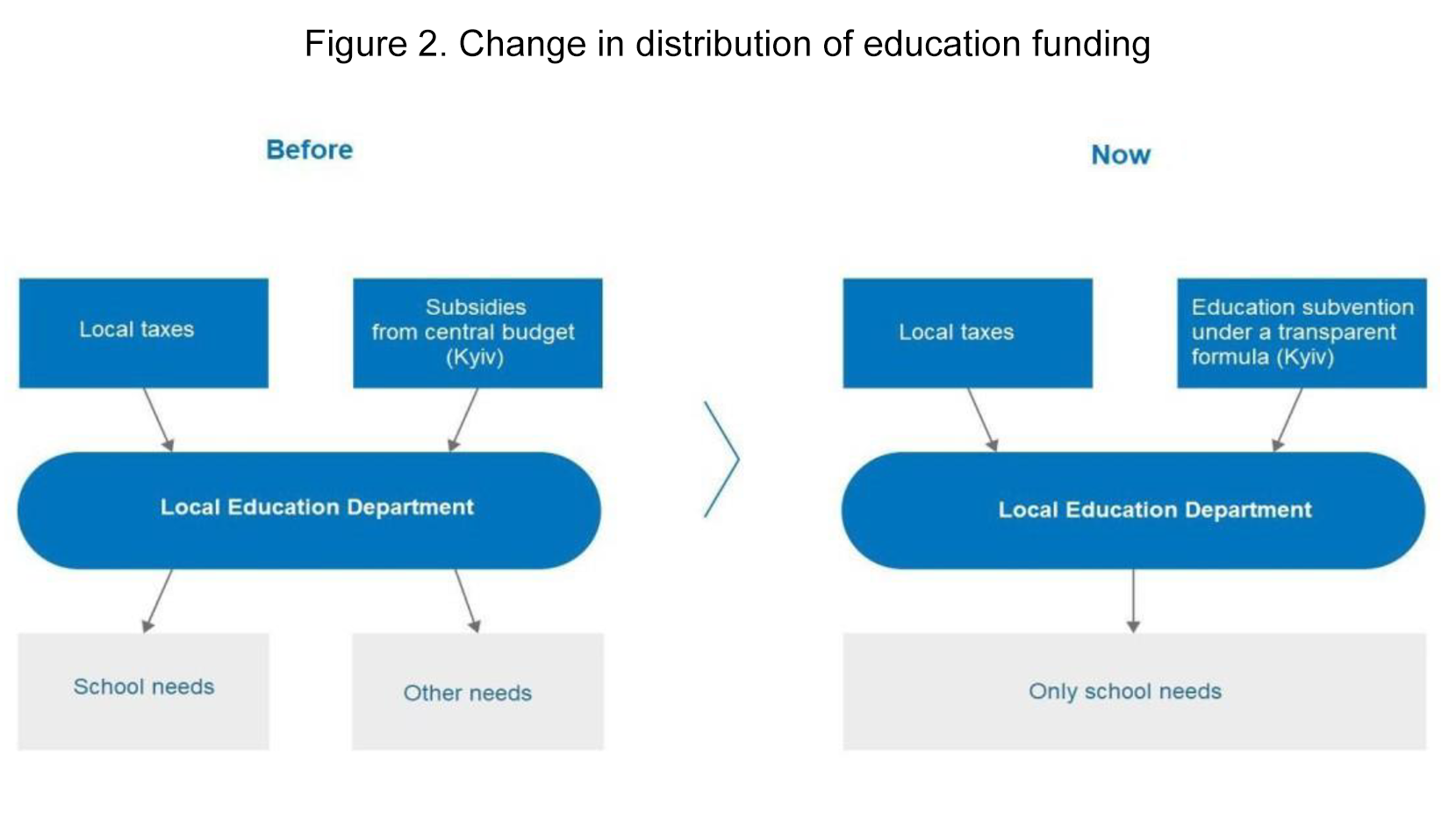

Until recently, schools were funded partly from local taxes and partly from the central budget, which was put together by the Ministry of Finance in the capital. The amount allocated by the government was often not enough for maintenance costs. The education department of the state administration on the ground, which managed the entire education budget, had the right to use a budget subvention to divert these funds to purposes other than schools.

School funding will continue to be partially covered by the central budget (because many districts would not be able to fully fund their schools even at a minimum level). However, the new education subvention — which replaces the old budget subvention — is calculated by a different formula, and the funds can only be used for educational purposes. Further, only the elected ATCs are given power to manage the subvention funds.

The shift of funding to the community level may help Ukraine break away from the previous system of planning and executing educational policy by bridging the gap between operational and financial management. In turn, this shift should lead to increased access to high-quality education across Ukraine, especially in the most remote areas. The participation of local municipalities and schools in the decision-making process in education should improve the distribution of public funds.

Optimization of the school network: What’s in the pipeline?

Decentralization enables local communities to make decisions about the opening or closing of schools based on their own capacities and needs. The optimization of school networks is now partially initiated by the central government, but a community may refuse to close even the smallest school if the population disagrees. The central government, however, encourages optimization through a new formula of education subvention, which provides more funding to schools with greater numbers of students.

School networks can be optimized by closing underperforming schools and arranging transport to and from the nearest schools. Communities can also open a “hub school” (usually a large school in the administrative center of the community) to compensate for closed schools. A hub school is a general secondary education institution with a higher legal status and more power compared to regular schools. Hub schools usually serve more than 200 students and have modern equipment for various subjects as well as highly qualified staff. Middle and high school students attend this type of school, whereas elementary school students go to nearby small schools.

Hub schools are supposed to be funded from both the state and local budgets, but ATCs can apply for grants for various needs, including for their schools. To ensure school access for all children, ATCs must arrange school buses for students and teachers who live away from hub schools. Elementary schools from neighboring villages are usually certified as hub school branches and supervised by the hub school principal.

The first few hub schools were created in Ukraine in 2016. The adoption of the 2017 Law on Education provided a legal basis for these schools. As of May 1, 2018, there were 519 hub schools established around the country. However, some parents of children whose schools are closed or whose children would have to attend newly created hub schools say they are concerned, afraid about the possible decline of their children’s academic performance due to more time spent on bus trips rather than homework. The capacity of ATCs to manage resources related to the relocation of students, such as finding the right number of buses and providing sufficient funds for fuel, is also questioned.

How Does The Decentralization Reform Work in Practice?

It would be premature to make comprehensive conclusions about the reform process at this stage. Some actions were taken at the community level — such as the creation of ATCs and the transfer of power to the local level.

Although the proper legislation for the transfer of power and funds to the community level was enacted, it will take time for representatives of state institutions to ease the grip on power and become accustomed to communities having the power to manage their own affairs. It will also take time for the communities to gain expertise and be sustainable enough to run themselves.

Creation of ATCs: Only half of Ukraine covered, roadblocks ahead

A number of ATCs were created in 2015, with “Pechenizhyn” ATC in Kolomyia district of Ivano-Frankivsk oblast the first. The ATC made the creation of an education department one of its priority tasks. The department registered as an independent legal entity to give it more autonomy when making decisions and signing documents. The community created its own methodology service, despite some resistance from regional authorities to the transfer of power. The newly created service is managed by community teachers and supervised by the school principal, not by regional state officials as it had before.

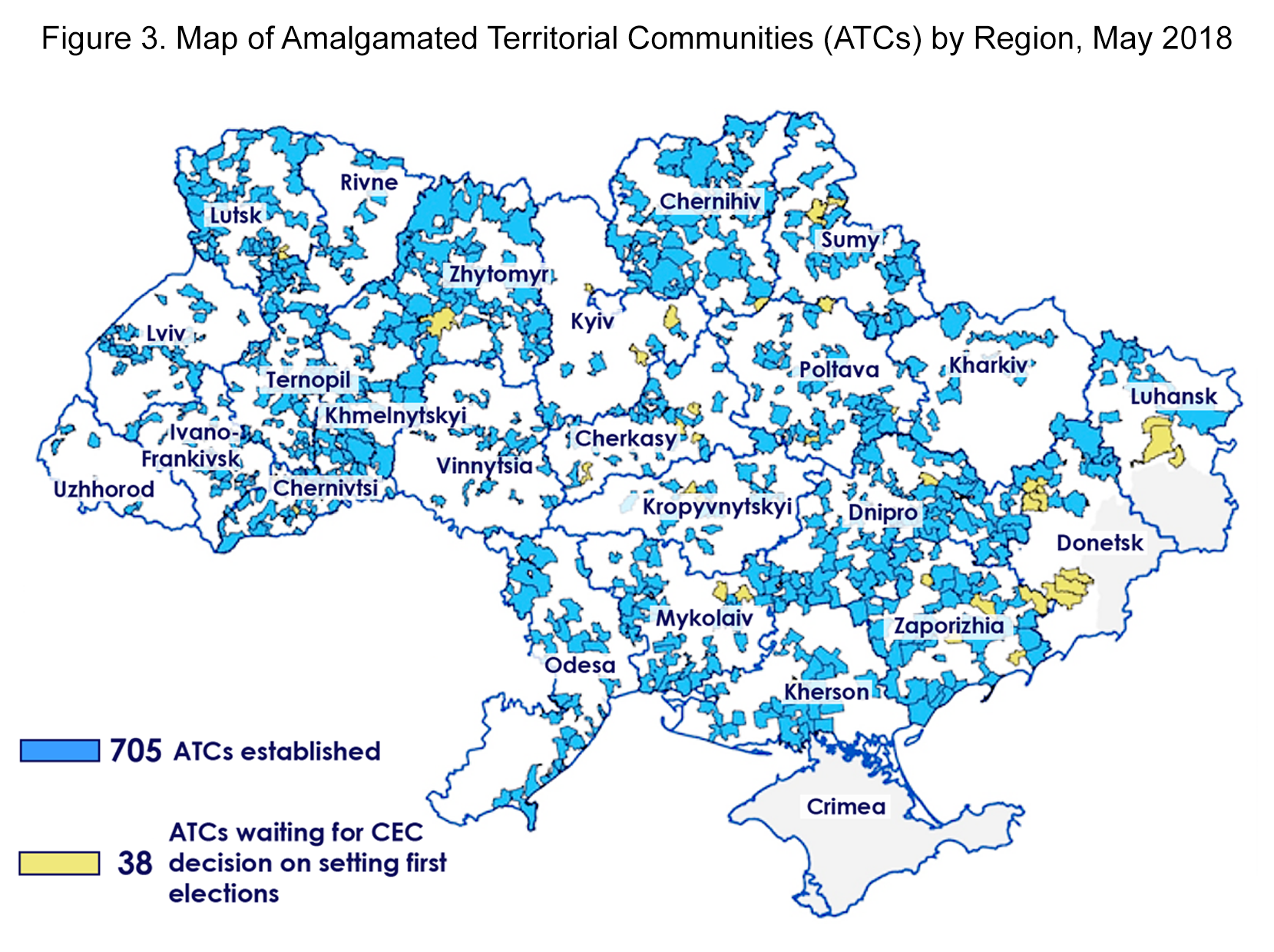

Source: Decentralization: https://decentralization.gov.ua; edited by CEDOS.

Despite a number of successful cases of transfer of power from the center to local communities, the overall process is slow. As of May 10, 2018, only 731 ATCs had been created in Ukraine, which leaves more than 50 percent of the country without an ATC. The forecast is that the number of ATCs will grow to 1,200. However, the final number is difficult to predict, as much depends on the readiness of local residents and the willingness of local governments to share power. In some regions the process of community amalgamation meets strong resistance from state-appointed officials. The very idea of power transfer is at times challenged. For example, in a recent interview in the Ukrainian media, Mr. Moskal, a powerful political figure and the governor of the Zakarpattia region, called decentralization unconstitutional.

The situation is changing in the districts where ATCs have been established and municipalities have gained more responsibility and control over decision making in education matters. However, the process has not been smooth when it comes to authorities ceding power to the ATCs. Regional and district administrations may try to stall the transfer of power to local communities, although doing so may be difficult to achieve with legal means. Experts interviewed for this paper claim that there have been cases when representatives of a state district education department would try to convince citizens of a certain community to keep the management of education issues in their hands, claiming that the ATC would be inexperienced. Capacity is also still weak at the community level when it comes to managing financial issues.

Optimization of school networks

Closing a school is never an easy or simple decision, especially when it is done by a community administration at arm’s length from its residents. However, local administrations are more inclined than their colleagues from the state administration to look for compromises and find suitable solutions for their own people. For example, the education department of the Baranivka ATC (in Zhytomyr region) conducted a school network analysis to examine the number of preschool students and children, recent population growth rate, distance between schools, road conditions between settlements, average costs per child in each school, etc. Based on the findings, the ATC management decided to close 2 of 15 schools in the community. The ATC’s education department then organized public hearings in villages where schools had to be closed. The ATC leaders convinced teachers and parents that closing the schools was a good decision. In exchange, the ATC promised to ensure the transportation of children to their new schools and guaranteed teachers’ re-employment.

Risks to Decentralization of Education Services

Political risks: Unpopular but necessary decisions under threat

Despite an initially successful start of both education and decentralization reforms, there are serious risks to be considered.

Ukraine will have both presidential and parliamentary elections in 2019. The unofficial electoral campaign has already started. Prior to these elections, the incumbent parliament may be less inclined to make unpopular decisions or adopt laws that would not bring immediate benefits to voters. Political analysts forecast that the next parliament may be taken over by populists who have no interest in supporting structural reforms. The new parliament is unlikely to dismantle the ATCs or halt education reform, but it may be unwilling to proceed with the adoption of laws needed to implement decisions adopted earlier. For example, the creation of an administrative division in between a community and an oblast (“a large district”) has not yet been resolved and requires a new law. It remains to be seen whether the new parliament will be ready to make this step.

There is a risk that the community amalgamation process will be left hanging in the air. Some in the government — be that at the central or the local level — resist the establishment of ATCs, according to interviews conducted by the authors of this paper. The 2019 elections may put this process in further jeopardy. In the areas without ATCs, the implementation of education reform may be hampered by the lack of authority and municipal resources. Unlike ATCs, district education departments usually are not interested in cutting the number of schools and setting up hub schools. Therefore, any areas without ATCs may lag behind the introduction of new education standards.

The local decision-making process does not differ much from the national one. Local populism may affect the optimization of the school network. Some candidates won local elections with a promise to keep all schools open, even when a closure would be justified. Although ATCs with a small number of school students will receive relatively limited funding under the new formula for education subvention, these incentives may not be enough to stop state representatives at the local level from misusing community resources to avoid confrontation with their electorate about school closures.

Last but not least, a number of education reform experts emphasize that the appointment of school principals for ATC schools may be politicized — that is, they may be selected based on party affiliation rather than merits.

Systemic risks: Will ATCs have enough capacity?

The ATCs’ low capacity is a major non-political risk. To date, the newly established ATCs do not have highly qualified and experienced personnel to take on their new tasks and properly manage financial resources. The central government and NGOs, with the help of Western donors, work on building the ATCs’ capacities, but this may take more time.

In conclusion, the coordination of the decentralization process with education reform allows for the creation an effective school network in Ukraine. The ATCs have more tools at their disposal to effectively manage schools at their level, and they were given the power to make decisions and allocate funds according to the needs of their communities. The reform is not complete, and there are certain political and systemic risks to be considered. However, Ukraine cannot afford to walk away from education reform, especially in areas where the central government has little reach.

What Could Germany Do to Help Ukraine?

The German government along with the governments of several other EU member states have been providing extensive assistance to Ukraine to help communities gain experience and expertise. In particular, the U-LEAD Programme was established to support the decentralization process. With the support of the program, more than 3,700 training sessions, workshops, conferences, and on-site consultations had been held throughout Ukraine by the end of 2017, reaching around 20,000 representatives from various municipalities. The main topics are operational planning, financial management, and human resource management for ATCs. The program has also organized 46 dialogue events and 10 media training sessions.

The answer to the question of what Germany can do to help Ukraine answer is twofold. Germany has been one of the most important supporters of reform in Ukraine. The authorities in Kyiv value this support and listen to Berlin’s advice. It is vital that Germany reminds the Ukrainian authorities about its commitments in the framework of the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement and the promises made to the people of Ukraine who demanded change in the 2014 Revolution of Dignity. Secondly, ATCs — already the recipients of extensive training programs from Germany and other European donors — need more capacity building to improve the implementation of education reform. Training activities should also be extended to areas where ATCs are not yet created or where the amalgamation process is taking time. Training for local state officials in the sphere of education is needed to ensure better cooperation between their institutions and the new communities.

Support Cedos

During the war in Ukraine, we collect and analyse data on its impact on Ukrainian society, especially housing, education, social protection, and migration