Project: Ukrainian Students Migration to Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, the Slovak Republic: human capital perspectives

Funded by International Visegrad Fund and The Kingdom of the Netherlands

Grant managing organisation: Institute of Public Affairs

Authors: Katarzyna Gracz, Anna Piłat, Justyna Segeš Frelak, Dominika Michalska, Agnieszka Łada

Concept of the project and methodology of the research: Yegor Stadny, Oleksandra Slobodian, Anastasia Fitisova, Mariia Kudelia

Review: Oleksandra Slobodian

Table of content

Immigration policies towards foreign students

Enhancement of human capital potential

Ukrainians students and graduates – numbers, profile, plans

Numbers of Ukrainian students and graduates in Poland

Profile of Ukrainian students and graduates in Poland

Motivation of Ukrainian students to study abroad

Readiness to take up employment in Poland

Attachment 1 – Methodology note

Attachment 2 – In-Depth Interviews Guides

Attachment 3 – Questionnaires for collecting statistics

Attachment 4 – Questionnaire for online surveys

Executive summary

Poland does not have a comprehensive, up-to-date migration strategy, combined with a policy of internationalizing the higher education, but the number of Ukrainian students is constantly growing. Young people from Ukraine are coming to Poland because of the lower costs of living and studying and better prospects for finding a job in this country. Higher education schools, especially private ones, carry out their own campaigns to attract Ukrainian students to Poland. At the same time, Poland still has a lot to do in order to make life and studying easier for foreign students, including the Ukrainians. The existing procedures do not always work in practice. Whereas the Polish labour market is interested in attracting qualified young people.

Foreword

In Poland we hear more and more about the shortage of qualified workers. A way to increase their number is to encourage young people from other countries to come to Poland. Those who are particularly valuable are the ones who know the language, the culture as well as the procedures and requirements for a given profession – that is, those who have completed their education in Poland. A group which in recent years has been particularly willing to come to Poland to work and study are the Ukrainians. However, Poland has not yet developed a uniform, concrete policy strategy addressed to this group. While various procedures concerning work or obtaining visas have indeed been introduced, their aim being, in theory, to make it easier for Ukrainians to start their career in Poland, the practice, however, is far from satisfactory and the activities of individual institutions are not consistent. At the same time, not only employers, but also universities see the young Ukrainians as their chance for development, or – for stopping the negative processes related to demographic trends. Therefore universities themselves are taking steps to encourage new secondary-school graduates to come to them to continue education.

For many years, the Institute of Public Affairs has been analysing both the changes on the labour market, the migration processes as well as the attitude towards selected social groups and foreigners in Poland. These studies clearly show that the issues concerning the presence of Ukrainians in Poland, their employment, perception and integration with the society must be treated as a whole. At the same time, it is important to pay attention also to the context of the Polish-Ukrainian relations and the fact that recruiting qualified workers in Poland means their shortage in Ukraine, whereas the development of this country is in the interest of Poland. The research whose results are described in this publication, refers, therefore, to the broadly understood issue of the presence of Ukrainian students in Poland and the challenges they have to face. At the same time, due to certain constraints, the study could not cover all the aspects, and therefore focuses on the crucial ones – the existing procedures and the opinions of the students themselves about their motivations and plans for the future.

These challenges are similar for the entire region, that is why it was decided to conduct identical surveys in all countries of the Vysegrad Group. Ukrainian analysts contributed to the contents of the surveys and the conclusions. Thanks to the cooperation between centres from five countries it has been possible to treat the subject comprehensively, including the double perspective – of the countries of destination and of the sending country.

The following text consists of two main parts. The first describes the legal provisions and the conclusions drawn from interviews with experts on migration policies, labour market and education. It presents the framework within which students and graduates from Ukraine operate. The experts – ministerial and local officials, analysts, representatives of universities and student organizations commented on the rules in force in Poland and described the procedures that candidates for students, students and graduates must submit to.

The second part introduces the results of a public opinion poll conducted among Ukrainian students and graduates of Polish universities. The survey was conducted on the Internet. More than 1000 replies have been received, which is a very high number for this type of study and allows us to treat the responses as reflecting the views of a significant number of students, even though such questionnaires are not of a representative character (the sample was not drawn in a representative manner). Details concerning the methodology as well as illustrations presenting the profile of the surveyed are included in the attachments.

We hope that this publication will help you get a picture of Ukrainian students in Poland and the legal framework within which they function. At the same time, we are aware that many aspects have not been sufficiently covered. These gaps are worth filling since this issue will remain highly topical in the years to come both in Poland and in the entire region.

Policies

Introduction

In the recent years Poland has suffered severe demographic crisis that is due both to the demographic decline and the emigration trends amongst the Poles in the working age. The consequences of this demographic situation are felt most vividly in the education sector and labor market. The most acute and severe effects of these tendencies are experienced by the private universities that run the risk of imminent closure or at least serious reduction of their operation. The foreign students are perceived, in this context as an important reservoir both of the potential students and, consequently, of the qualified working force that is missing in the Polish market. Although the demographic trends are definitely not new but rather augmenting and the results thereof accumulating in time – there is hardly any governmental migration strategy that could be perceived as well-tailored, real needs-oriented, comprehensive and coherent. However, the official position of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education is rather straightforward – as its Minister put during the last conference “Foreign students In Poland” that took place in January 2018 – „There is no other possible notion than internationalization of education in Poland. The alternative is stagnation, which means – setback. I am quite sure nobody here takes this scenario into account […]. However, the road ahead of the universities, as well as the government that will support the Academia in this endeavor, is really long.” That seems to be true in this context. There are some fragmented policies on the governmental level both in the fields of migration and education, however they could hardly be seen as complete and exhaustive migration strategy. This negative phenomenon of governmental inaction is recently further enhanced by the ideological concerns that are being publicly stated by the representatives of the ruling party, Law and Justice, who perceive the immigrants as a potential threat to the public order and safety and therefore are unwilling to design a comprehensive governmental migration strategy. The present government first suspended and in March 2017 subsequently abolished the „Polish Migration Policy” document drafted by the previous government. In the justification of this step Jakub Skiba, secretary of state in the Ministry of the Interior and Administration stated: „This is a pragmatic position rather than an ideological one. In our opinion an ideological approach that is based on a vision of multiculturalism and broad migration absorption is incorrect.”

Although the anxieties that easily grow on the fertile ground of conservative far-right ideology of the ruling party do not primarily refer to the Ukrainians, but are rather aimed at the immigrants of the Muslim background – all in all the current political situation in Poland does not favor the development of the comprehensive migration strategy that would tackle the demographic crisis neither in the sector of education, nor on the labor market.

By no means should this observation lead to the conclusion that no steps are being taken on the Polish side to encourage Ukrainian youth to study and work in Poland. Quite to the opposite, a lot of effort is put into promotion of the Polish institutions of higher education in Ukraine and other countries. However, this task is mostly tackled by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education and the universities themselves that perceive Ukrainian youth as the potential that might save their existence both in the short and in the long run. The Ministry of Science and Higher Education is running the strategy which is strongly based on the concept of, first of all, necessity of increasing the level of internationalization of the education in Poland and, second of all, improving the quality of higher education in Poland therefore it will be more and more attractive for foreign students. Having said that, it should be underlined that there exist many actions of the governmental nature, running by the Ministry, which although not exhaustive and of the fragmentary nature do support the universities in their measures to internationalize the sector of Polish higher education.

Selection of human capital

As already mentioned, there no effective national migration strategy in Poland. The present government first suspended, and in March 2017 subsequently abolished the “Polish Migration Policy” document written by the previous government. There is also no effective migrant integration program at the national level, regional or local level. Only those who have been granted refugee status or subsidiary protection qualify for participation in the annual Individual Integration Program (Indywidualny Program Integracji – IPI), while other groups of migrants (including students) are not entitled to state funded support and rely on NGO assistance. Persons who have obtained permission for so-called tolerated stay are deprived of the state funded integration assistance, only having the right to assistance in the form of shelter, food, necessary clothing and designated benefits that cover costs of the purchase of food, medicines, household goods, etc. The orientation courses (including information on legalization procedures) are sometimes provided by schools in the cooperation with ngo sector for example but there is no obligatory program offered to foreign students. The lack of the orientation courses or their limited availability as well as ineffective practical support is considered as big disadvantage of the internationalization process in Poland. It is worth mentioning that the political change resulting from the elections in 2015 has put the discussions on the Polish integration policy on hold. It should also be underlined that the low priority given to the issue of integration is manifested not only by the suspension of work on integration policy but also the reduction of funding for the NGO sector in these areas.

However, even if there is no migration policy in force the central and local government are active in the field of the attracting of the foreign students basing on their own agenda. The need of attracting and recruiting foreign students, even after the migration policy agenda of the new government has change significantly, is still one of the most important issues on the agenda of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education. This agenda, as it was also stressed by experts, did not changed in the meantime, even after change of the government. The general scope, during creating the previous Polish Migration Policy and during drafting the new one, remains the same. It is based on the concept of necessity of increasing the level of internationalization of the education in Poland and improving the quality of higher education in Poland therefore it will be more and more attractive for foreign students. The Ministry is also perfectly aware that the interest in studying in Poland among foreigners is diminishing (for example due to demographic decline in Ukraine) and it must be consciously supported by the Ministry/Government in Poland so universities will not have to struggle with the lack of student in the following years. An expert from the Ministry defined the last few years when the number of foreign student has grown dramatically “an education bubble” that will be soon over if there will be no strategic action taken upon on the governmental level.

The Ministry openly approves simplifying of the legalization rules for students as well as all measures supporting the graduates on the labor market proposed by the Ministry of the Interior. It also offers direct support for public and private universities, for example by the training of the university staff. One of the respondents responsible for recruiting foreign student stated that, as a worker of international relations Department at the University, he obtained a significant support from Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education. For instant, he attended trainings organized by the Ministry that were to educate workers from international departments and recruitment departments from whole country in the way to recruit successfully students from abroad. However, the respondent didn't value high the education fairs supported by the Ministry. He found the education fairs organized by private companies in Ukraine much more effective.

Furthermore, a significant role play the regional governance (urzędy wojewódzkie, wojewodowie) in this regards (as experts state – it is highly more valuable then role of central government). For example one respondent took part in few scientific and business trips organized by the voivodeship and he found them very valuable.

Therefore, it might be argued that although there is no comprehensive governmental migration strategy in force nowadays in Poland nor there is any political will in that respect – many policies and regulations in the field of education do in fact encourage Ukrainian students to take up their studies in Poland. This observation is consistent with the fact that although Poland misses a coherent migration strategy – it does currently apply its Development strategy of higher education in Poland by 2020 which measures for achieving the strategic goal of Mobility which includes among others increase in the percentage of foreign students.

Still, the most visible steps in promoting higher education institutions to Ukrainians are being taken by the universities themselves in order to promote studies in Poland to the Ukrainian youth.

Still, there is no strategy on engagement of Ukrainians, or any other foreigners, in the host society. The exception is the Polish Card (Karta Polaka) that allows people of Polish origin to obtain a long-term visa, with entry/exit rights that can secure legal employment without having to obtain a work permit, and access the Polish education system free of charge. Since 2014 the holder of Polish Card can also settle in Poland and get the permanent residence card. Since 2 of September 2016 holder of Polish Card who settle in Poland after one year can acquire Polish citizenship. Since 1 of January 2017 those people will get the financial assistance for first 9 months of residence in Poland.

However, except specific measures aimed at holders of Polish Card, there are no others policies towards foreign students. Consequently, there is no integration polices, or even state programs aimed at this group. One of the respondents stresses the serious problems that he observes as the student migration has been growing so rapidly in the last few years. He states that, these problems are directly connected with growing Ukrainian group in Polish cities, which phenomenon is considerably new for this community. Firstly – he observes growing language problems that Ukrainian students have – he knows few cases when after finishing the Bachelor Program students have no ability to speak and write in Polish. That is strongly connected, on the other hand, with lower performance of the students. Secondly, he observes tendencies to stay only within the group of Ukrainian students and lack of ties with Polish students/other foreigners at the University. As a reaction to these tendencies the Ukrainian Student Association organizes several activities both for Ukrainian and Polish students and tries to conducts all courses in Polish.

Immigration policies towards foreign students

The most important is the principle according to which as a rule all foreigners are entitled to take up studies at Polish tertiary education institutions. The rules for their admission, however, and conditions of studies at public higher institutions vary depending on the foreigner’s legal status in Poland. In some cases foreign citizens who study in Poland are eligible to receive the same benefits as Polish citizens (including free tertiary education). In case of the Ukrainian students this principle applies to:

-

Individuals who have received a permanent residence permit to settle on the territory of Poland,

-

Individuals in possession of Polish Card (Karta Polaka),

-

Individuals with refugee status or secondary protection obtained in Poland,

-

Individuals with a long-term EU resident permit issued in Poland.

In case of Ukrainian students, from all groups mentioned above the most common are students in possession of Polish Card and individuals with a long-term EU resident permit issued in Poland. However, the most typical pattern of legalization of stay is firstly – obtaining a visa, then – obtaining short-term residency in Poland. To obtain a visa one has to deliver the documents that explain the purpose of visit – in this case – confirmation of the acceptance on the Polish University or in case of continuality on of the studies – proof of being in the University program. If the studies are paid – the student must also deliver the proof of payment for the first term or the whole year or show sufficient means to cover in on the bank account. Besides that the applicant should show the sufficient means to cover living expenses in Poland and proof of adequate housing (Schengen visa) and confirmation of readiness to leave Schengen territory upon visa expiry.

The Act on Foreigners from 2013 certainly simplified the provisions on residence permits for the purpose of higher education. That was one of the most crucial steps in adapting migration policy measures to consciously attract foreign students to study – and what it most important – work in Poland after they graduate. Ukrainian students (but only those who are full time students) are equal in rights as Polish students with one significant exception – they have to pay for their studies (this rule do not comply with the bearers of the Card of Pole). Ukrainian students firstly apply for the student visa in their home country – then they are obliged to apply for the temporary stay permit in the voivodeship office. Their first stay permit can be granted for a maximum of fifteen months, the next one – up to three years, and in the case of graduates, the residence permit also covers a period of three months after the date of graduation. In this respect, this regulation is somewhat more favorable than the provisions of Council Directive 2004/113/EC of 13 December 2004 on the conditions of admission of third-country nationals for the purposes of study, exchange of schoolchildren, unpaid training or voluntary service.

Persons having the residence permit for a long-term resident of the European Union issued by another Member State which intends to commence or continue its studies or vocational training in Poland are free access to the Polish education system. It is worth noting that the Act provide separate residence permit for such persons, for which foreigner is not expected to fulfilled any conditions other than source of income, health insurance and place of residence. A person who does not have the right of permanent residence acquired in another Member State to apply for a residence permit in Poland to study should document the admission, health insurance, place of residence and source of income. The amount of monthly income should be higher than the amount of income entitling to benefits from social assistance provided for in the Act of 12 March 2004 on social assistance (Journal of Laws of 2017, item 1769 and 1985), with reference to foreigner and each dependent member of the family. The last condition may be a significant obstacle to undertaking studies in Poland. Students must prove that they have the means, firstly, to pay for their studies; secondly, to cover the cost of living for fifteen months (at least 543 PLN/125 EUR a month); third, to cover the cost of returning to their country of origin from PLN 200/50 EUR to 2500 PLN/583 EUR).

This regulation is shown as a one of the main pitfalls of this particular migration policy – it is not enough for students to show that they have steady income or they are monthly supported by their parents for instant – they have to gain all the amount on their bank account in the moment they are applying for resident permit. Above that residence permits are also granted to a foreigner who intends to take a preparatory course to study at the university in Polish language.

It seems that even if the foreigner does not qualify for the full time free program at the Polish public university the considerably low level of tuition fees (as compared to Western European institutions) might be perceived as encouraging by the external students for the fees range from EUR 2000 to 6000 per year. Moreover, foreigners of Polish origin, who take up paid studies are entitled to reduced fees (30%) and at the justified request of the foreigner, the rector of the university may reduce the fee or exempt it completely. It is worth mentioning that candidates for the university programs who do not speak Polish are eligible for preparatory language courses that last 9 months and are organized by many public universities [e.g.: Kraków (Jagiellonian University and Cracow University of Technology), Lublin (Maria-Curie Skłodowska University), Łódź (University of Lodz), Rzeszów (University of Rzeszów), Katowice (University of Silesia), Wrocław (Wrocław University of Technology)]. It is also of utmost importance that the recent Act on Foreigners from 2013 simplified the provisions on residence permits for the purpose of higher education including the permits for the foreigners who intend to take a preparatory language courses. The novel procedures are described in details in the section of the report entitled Immigration policies towards foreign students. It is also worth noting that not only the potential students but also their relatives have had an access to Poland simplified as special short term Schengen visas are issued for family or friends of the Ukrainian students who have a valid residence status in the territory of the Republic of Poland.

The legal principle of mutual recognition of educational systems that stems from the bilateral agreements between Poland and Ukraine is also of crucial importance for the Ukrainians willing to study in Poland. The current Agreement between the Government of the Republic of Poland and the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine on the mutual recognition of academic documents on education and equivalence of degrees, signed on April 11, 2005 (entered into force on June 20, 2006) guarantees to people who have received education in one of the states parties of this agreement the possibility of continuing education in institutions of the other country (so called “recognition for academic purposes”). However, the statement of equivalence of diplomas and academic degrees obtained in Ukraine after June 20, 2006 and the diplomas of a doctor, dentist, pharmacist, nurse, midwife, veterinarian and architect issued before that date is possible only after the process of nostrification.

Another legal principle that strongly motivates many Ukrainian citizens to study in Poland is the rule according to which foreigners who may take up studies according to the same regulations that apply to the Polish students [e.g. holders of Polish Card] are eligible for the scholarships funded by the public budget. There are several types of grants and allowances available to this category of Ukrainian students. The most important are:

-

social scholarships,

-

special needs scholarship for handicapped students,

-

merit scholarship for academic results or sporting achievement [e.g. Rector scholarship],

-

ministry of education scholarship for academic merit,

-

meals allowances,

-

accommodation allowances.

Foreigners who are not eligible to apply for the above scholarships may nevertheless apply for the Polish government scholarships that are granted pursuant to bilateral agreements.

Holders of Polish government scholarships can study in Poland for free. International agreements determine annual limits of places. Moreover, Ukrainian students are eligible for the governmental scholarship and grant scheme drafted specifically for the support of the citizens of the Eastern Partnership countries – the Scholarship Program for them, Stefan Banach that has been launched in 2013 in cooperation between the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Poland. Scholarships offered within the programme include free both 2nd degree studies (Master studies) and 3rd degree studies (PhD studies) conducted at public universities supervised by the minister responsible for higher education.

Apart from the governmental funds, Ukrainian students are eligible for many intergovernmental and non-governmental study grants for studying in Poland, the most prominent being Lane Kirkland Scholarship Program,Visegrad Scholarship Programme and Scholarships for Master level Eastern studies .

It is also worth underlying that as of May 1, 2015 it is possible for all the students enrolled for full time courses or doctoral studies to take up employment without a work permit (including visa holders without a residence permit). Such a regulation can be undoubtedly considered as encouraging to undertake studies in Poland, because students already during their studies are able to gain experience in companies operating in the Polish market. It could also be argued that the easy access (the same as for other Polish citizens) to public health services granted to foreign students insured in the National Health Fund might be perceived as an encouragement to study in Poland.

Furthermore, the period spent at the Polish university might be partially included to citizenship requirements of duration of stay which might also work as an incentive for the Ukrainians to study in Poland.

Moreover, there are some actions being taken on the governmental level to directly promote Polish universities abroad. For instance the Ministry of Science and Higher Education, together with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Foundation for the Development of the Education System and the Conference of Rectors of Polish Academic Schools, is implementing a plan to promote Polish higher education abroad, including organizing Polish stands under the banner of the "Ready, Study, Go! Poland / Research & Go! Poland at conferences and educational fairs in the world.

Enhancement of human capital potential

Experts agreed the latest changes in the law brought significant and positive changes for foreign student in Poland. They agree that Polish migration’s law regulations have several simplifications concerning not only students, but also graduated willing to stay and work in Poland. However, many solutions do not really work in the practice or some aspects of them are criticized. As one of the respondents stresses: Ruling regulations are good enough to attract a large number of foreign students, however I would recommend simplifying and shortening bureaucratic procedures of obtaining residence permits. The other expert, a representing Ukrainian students, stated that even though Polish law regulations have several simplifications concerning both workers and students, they are still one of the most challenging aspect of everyday life of Ukrainian students in Poland.

Obtaining residence permit and access to the labor market

Experts strongly stresses that both stages of legalization of stay in Poland, firstly – applying for visa – due to the overloaded consulates and visa centers on Ukraine and secondly – applying for temporary stay (Karta Pobytu) – is very burdensome for students and sometimes can put their studying on hold. It also strongly depends on the practice of the particular voivodeship office, some process more, and some – less efficiently. As respondents directly put it

“If everything is standard – it's not extremely bad (even though the waiting period for obtaining Karta Pobytu could be up to 8 months!), but if anything non-standard happens: for example if the student fails some of his exams and has to repeat the year – the legalization system is extremely non flexible. I know many cases of student who even that they tried to be as accurate as they could – wasn't able to prolong their legal stay in the country or problems with legalization significantly prolonged theirs studies.”

The respondent mentioned many cases when, for example, students with no Karta Pobytu have to go back to Ukraine and then he cannot return to Poland to pass his exam on September (on the second round of exams) because consulate will not issue a student visa (students visa are issued only to student on their first year of education). In addition, foreign students’ progress at university is assessed while applying for another residence permit. A student who has been forced to repeat a year may receive negative decision for subsequent years of study precisely because he or she has not completed a full year of studies.

Not all the asked experts shared, however, such opinions. One of the responders, responsible for the recruitment strategy of the one off the biggest Polish private university stresses that he sees the significant problem with issuing the visas for foreign student – but in his opinion this problem does not cancers Ukrainians. He stresses that there is no significant challenges considering the migration law. In the respondent’s opinion students from Ukraine do not have serious problems with obtaining the Polish visas. Those problems are much more visible in case of students from Asia: especially students from China and Vietnam. The respondents stresses that the Polish Embassies and Consulates in Ukraine received a positive signal from Polish government (strategic policy) to issue visas to Ukrainian students. Therefore the respondent don't see problems in obtaining visa, he sees it however, in the next stages of legalization process when students are already in Poland. That is certainly serious problem for many students studying at the private universities. The respondent knows cases when the legalization of stay was so burdensome for some students that they have resigned from studying in Poland at all. At the same time, in expert’s opinion Ukrainians face the same situation on the labor market as Polish graduates (if, of course, they acquired sufficient Polish language proficiency during their studies).

After finishing of full time studies in Poland Ukrainian students are entitled to obtain a permit to stay with an aim of looking for a job for one year and what is of very importance they do not need work permit. However, challenges that may arise concern students studying part-time. In case of part-time studies there is a necessity of obtaining work permit by employers. It is obvious and visible that education policies towards foreigners influence the migration situation in Poland, the same as towards foreign graduates.

As already mentioned the access to labor market is connected with the type of course (e.g. full time or part time). As of May 1, 2015 it is possible for all students of full time courses or doctoral studies to take up employment without having to obtain a work permit including students without a residence permit (having visas) have been allowed to work without a work permit (students of full time course with a residence card were already entitled to work without a permit). Such a regulation can be considered as encouraging undertaking studies in Poland, because students already during their studies are able to gain experience in companies operating on the Polish market. Yet, students not enrolled on full time course have not given free access to labor market and need to apply for work permit and do not have to pass a labour market test. Employers who employ people, who are studying until the age of 26 under contract, do not have to pay contributions to the Social Insurance Institution. Students, but also persons having limited earning are entitled to tax – free allowance. For foreigners finishing studies in Poland, the state offers several possibilities for legalization of residence. A graduate may obtain the right to stay in connection with work if he has found an employer intending to employ him or the right to stay for a job search. It also should be noted that their ‘student residence permit’ is valid for three month after the graduation.

Above that, what is extremely important in this regard, after finishing of full time studies in Poland for the duration of one year and what is of very importance they do not need to apply for the work permit. The respondents do not agree whether this transitory year is sufficient to significantly improve the position of the foreign graduates on the Polish labor market. Part of the respondents agree that this transitory year is long enough to find a solid, full-time job and legalize of stay upon this employment. The others, on the other hand, argues that specify of the Polish labor market which generally does not offer much stability to the young employees (they are usually employed on term-contracted not on a pay-roll) – does not offer them chance to achieve this level of stability within only one year.

Universities’ actions enhancing the recruitment of the Ukrainian students

Both public and private universities in Poland perceive Ukrainian students as important for the future of Polish education both from the financial and academic perspective. The financial perspective is especially important for the private universities that with the recent demographic crisis in Poland do not manage to attract enough Polish students and therefore seriously rely on the inflow of foreign students. Ukrainians are perceived as the best group for the process of internationalization of Polish universities due to their cultural and linguistic vicinity. Representatives both of the public and private universities interviewed in the research underlined that the Ukrainians are easily integrated in the students’ groups, learn Polish very fast and do not as a rule require much help in terms of integration in the wider Polish society. This makes the Ukrainians one of the most required groups on which most of the Polish university recruitment strategies for foreigners are focused. Moreover, for some higher education institutions, such as university in Wroclaw or Warsaw – cooperation with the Ukrainian academia seems the most natural due to the common history and roots of that universities. On the other hand the geographic vicinity of Lublin also makes Ukraine the most reasonable destination for the promotion of the university based in that city.

The representatives of both private and public universities admit that they actively reach for the candidates from Ukraine both during the educational fairs in Poland and in Ukraine. Some universities, mostly private, hire ethnic Ukrainians to work on their account throughout the whole academic year in order to attract students from Ukraine. Moreover, some private universities admit that they actively cooperate with the recruitment companies based in Ukraine and offer them a given percentage of the tuition fee (usually 10%) for each successful recruitment of an Ukrainian student.

There are numerous actions taken both by the universities on their own or in cooperation with governmental and non-governmental actors focusing on the promotion of the tertiary education in Poland.

The most successful seem to be both "Study in Poland" and the "Ready, Study Go! Poland " actions that are aimed to promote Polish universities abroad and Poland as a country of educational migration. As part of the program "Study in Poland", conducted by the Conference of Rectors of Polish Academic Schools together with the Perspektywy Education Foundation, further editions of the guide to universities are being prepared, presenting the program of higher education institutions and their English and Polish offer. As part of the program, the promotion of Poland at international education fairs is also available, as well as the Study in Poland internet platform, available in English, Russian and other languages. It is worth mentioning that the recruitment strategies differ in between the Ukrainian regions: in Western Ukraine the promotion of Polish universities occurs somehow more naturally and spontaneously through the relatives’ and friends’ advertisement therefore more effort into structured strategies is put for the recruitment of students in the Eastern Ukraine.

Although active presence at the international education fairs seems to be the most popular strategy in the field of self-promotion – some universities come up with more original solutions such as open house days both for the candidates and their parents. Some respondents representing private universities admitted that numerous actions are taken at their institutions that are aimed at recognition of the Ukrainian students in the overall students cohort such as nomination of special Ukrainian reps in the students self-governing organizations or a celebration of the Ukrainian Day at the premises of the University. Such acknowledgment is also aimed at indirect promotion of the given universities amongst the Ukrainian youth.

Policies coherence

In conclusion it should be stated that although Poland currently misses a comprehensive and meaningful migration policy and the general political climate does not encourage the development thereof – the educational policies and overall mobility principle encourage Ukrainians to take up studies at the Polish institutions of the tertiary education. Ukrainian students are perceived both by the governmental institutions responsible for education as well as by the universities themselves as an important asset that can save Polish tertiary education in the period of demographic crisis. Therefore both the governmental and university agencies actively promote Polish educational institutions in Ukraine.

However, a more comprehensive governmental strategy is needed because the so far implemented ad hoc actions lead to many unintended results such as mentioned by the respondents common trouble that although foreigners are strongly encouraged to study in Poland – no action is taken to educate the university staff to prepare them for the challenges of the multicultural environment in their institutions.

Ukrainians students and graduates – numbers, profile, plans

Numbers of Ukrainian students and graduates in Poland

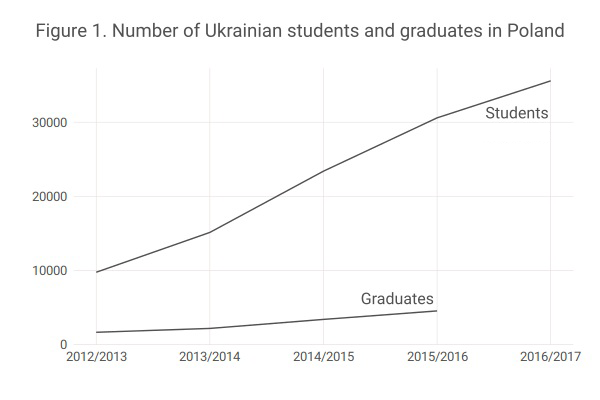

According to Polish official statistics the number of Ukrainian students and graduates is constantly increasing. In 2012/2013 there were 9 747 students, in 2013/2014 the number already increased to 15 123. In 2014/2015 Polish universities had 23 392 students and in 2015/2016 – 30 589. The newest data for 2016/2017 shows that 35 584 students from Ukraine were studying at Polish universities.

Similar increasing trend applies to Ukrainian graduates, where in 2012/2013 there were 1 641 Ukrainian students who graduated from Polish universities and 2 163 in 2013/2014. Another academic year (2014/2015) noted 3 380 graduates and data for 2015/2016 shows that the number increased to 4 526. There is no data of the number of graduates in the last academic year available.

Source: Own calculations based on Statistics Poland: Education, Archive

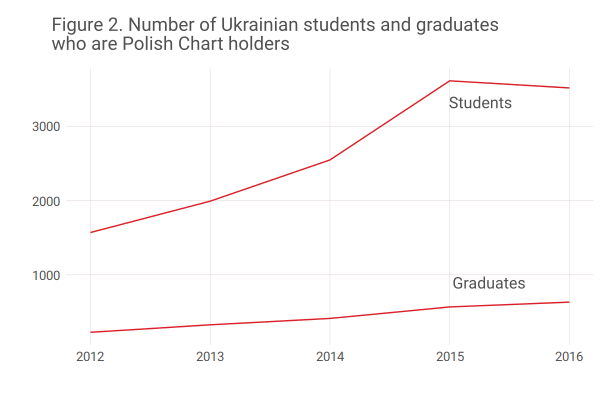

Some Ukrainians migrating to Poland have Polish roots and therefore are holders of the so-called Polish Chart. Statistics include this group in separate report. It indicates that: In 2012 there were 1 570 students granted the Polish Chart, in 2013 the number slightly dropped to 1 993. In 2014 Polish universities admitted 2 549 students with this document and in 2015 – 3 616. The data for 2016 is also preliminary, however it shows that in Poland was studying 3 520 Ukrainian students with Polish Chart, so more than double as much as four years before. So, also these numbers show, how high is the increase of the overall number of Ukrainian students in Poland since 2013, so when the Euromaidan took place and the war in Ukraine started.

Numbers of Ukrainian graduates with Polish Chart is higher by each year, where in 2012 there were 224 such Ukrainian students who graduated from Polish universities, 325 in 2013 and 411 in 2014. Another year noted 566 graduates and preliminary data for 2016 shows that the number increased to 631.

Source: Own calculations based on Statistics Poland: Education, Archive

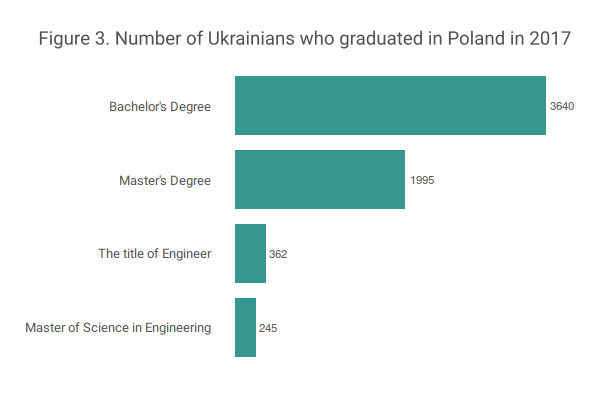

Most recent data recorded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education indicates that the number of graduates with higher education (engineer, bachelor, master, master-engineer) in 2017 was 6242. Most people, that is 3640, completed their studies with a bachelor's degree, while with a master's degree – 1995. Ukrainians who obtained engineering qualifications that year are 362 people, while the title of Master of Science in Engineering was awarded to 245 students. These numbers are constantly growing, starting from 2014, to 2017.

Source: Ministry of Higher Education 2018

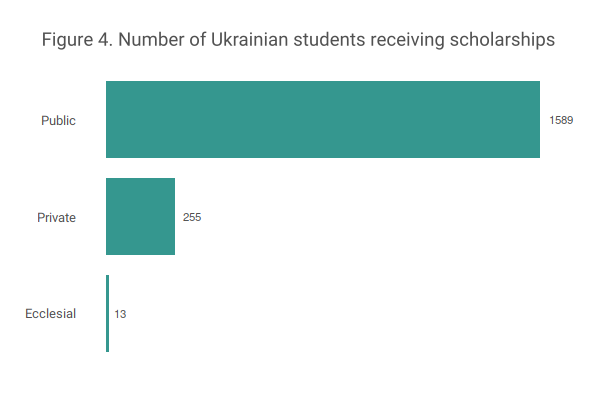

According to the latest data (2018) of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education, the number of Ukrainian students receiving scholarships is 1857. It is over 60% of the total number of foreign students receiving funding for studies in Poland. The most common type of scholarship received by Ukrainian students is the public scholarship and the number of its beneficiaries is 1589, while the number of non-public scholarships is 255, and the number of church scholarships is 13.

Source: Ministry of Higher Education 2018

Profile of Ukrainian students and graduates in Poland

Some insights who is coming to Poland are given in the opinion poll. However, one must remember, it was not a fully representative study, as the respondents were not chosen in a representative way, but decided to participate in the study by themselves. Still, the great number of answers (1055) lets formulating conclusions and drafting a general picture of Ukrainian students in Poland.

Among the respondents the biggest groups are the current students (83%) – people who realize a full programme (bachelor or master) at one of the Polish universities. The rest 17% are the Ukrainian graduates who obtained a diploma from a Polish university. Two thirds of all respondents have no Polish origin (67%), however, nearly one third claim their grandparents were born in Poland (31%). The clear majority still have close relatives living in Ukraine. Also the majority of the respondents have been living in Poland already long enough to collect needed experience to assess better their situation in the country – 29% have been living 1-2 years and 29% 3-4 years. The age of the respondents vary, but the largest group – 42% – consist of those 18-20 years old, followed by the 21-23 years’ old (32%). Every fifth respondent is older.

Among the ones who have already graduated from a Polish university there are both people who had stayed in Poland 3-5 years (34%) and 1-2 years (32%), as those who stayed longer: 5-8 years (29%). The largest group among them obtained the diploma in 2017 (35%) and it was usually a master degree (65%), followed by bachelor (28%) and a phd (7%). After the graduation three fourth of these respondents stayed in Poland (75%), when every fifth came back to Ukraine (20%). The numbers stay nearly unchanged when asked about current place of living (17% claim to live in Ukraine).

Motivation of Ukrainian students to study abroad

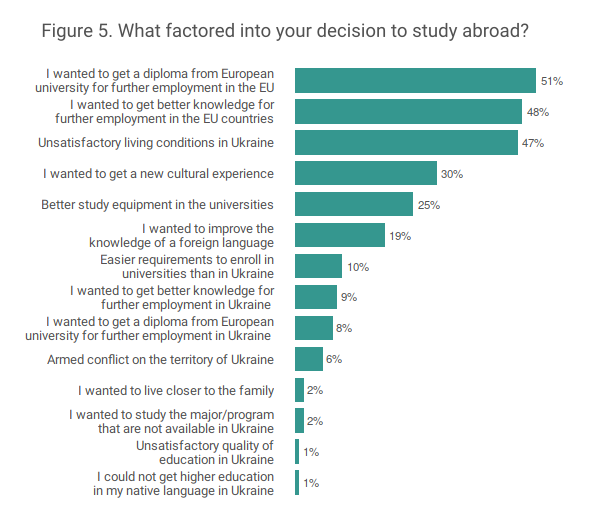

Students asked to choose three aspects that factored into their decision to study abroad claim that they wanted to get a diploma from a European university for further employment in the EU (51%), or to get better knowledge for further employment in the EU countries (48%). Also unsatisfactory living conditions in Ukraine (health care system, transport infrastructure, housing market etc.) is ranked high with 47%. The need to get a new cultural experience (30%) and the fact of a better study equipment among the Polish universities (25%,) and improving the knowledge of a foreign language (19%) are not the main reasons, however, still important for some young Ukrainians. Better regulation for further employment in Ukraine (9%), and a diploma from European university for further employment in Ukraine (8%) as well as armed conflict on the territory of Ukraine gathered 6% of the responses do not seem to be crucial for the majority of Ukrainian students for their motivation for studying abroad.

Source: Ukrainian Students Migration to Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, the Slovak Republic: human capital perspectives, 2018. N=1055

Note: Respondents were asked to choose up to 3 answers from the given list.

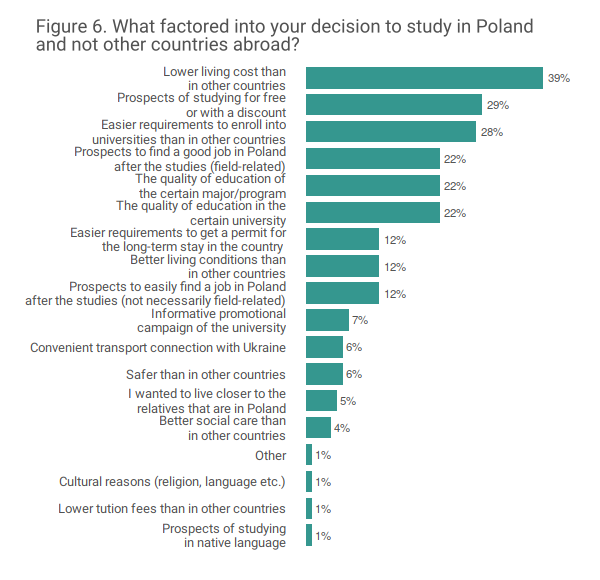

Poland as a country of destination was here a pragmatic choice. The main reason why the Ukrainian students decide to enroll to the Polish university is lower living cost than in other countries (39%), followed by prospects for studying with the discount (29%) as well as easier requirements to enroll into the universities than in other countries (28%). The students also indicate prospects to find a good job in Poland after the studies (field-related) , the quality of education at the certain university, and the quality of education of the certain major/program (22% each). Such indicators like prospects to easily find a job in Poland after the studies (not necessarily field-related), better living conditions than in other countries (health care system, transport infrastructure, housing market etc.), easier requirements to get a permit for the long-term stay in the country (12%) seem not to be the most relevant while going to Poland. Neither informative promotional campaign of the university (7%) does matter for many while deciding themselves for Poland.

Source: Ukrainian Students Migration to Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, the Slovak Republic: human capital perspectives, 2018. N=1055

Note: Respondents were asked to choose up to 3 answers from the given list.

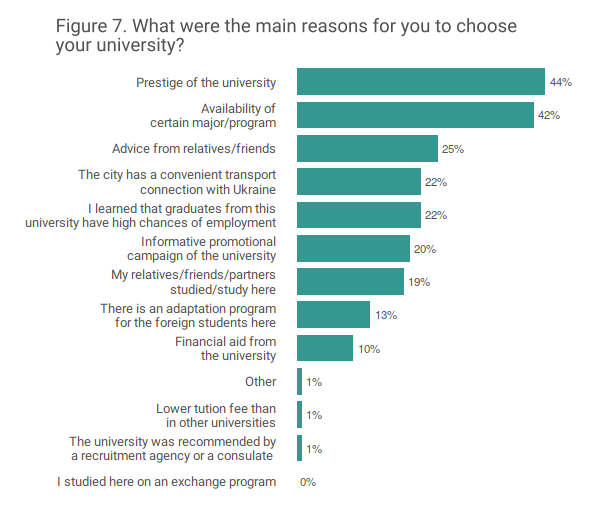

By the decision which university should they chose respondents orient themselves on its status value (44%) and availability of certain major/program (42%). For every fourth advice from relatives/friends (25%) does matter, as well as a belief that graduates from the particular university have high chances of employment (22%). The same number takes notice if the particular university is located in the city which has a convenient transport connection with Ukraine (22%). For every fifth informative promotional campaign of the university (20%) and the fact that the respondents’ relatives/friends/partners studied/study there (19%) is helpful.

Source: Ukrainian Students Migration to Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, the Slovak Republic: human capital perspectives, 2018. N=1055

Note: Respondents were asked to choose up to 3 answers from the given list.

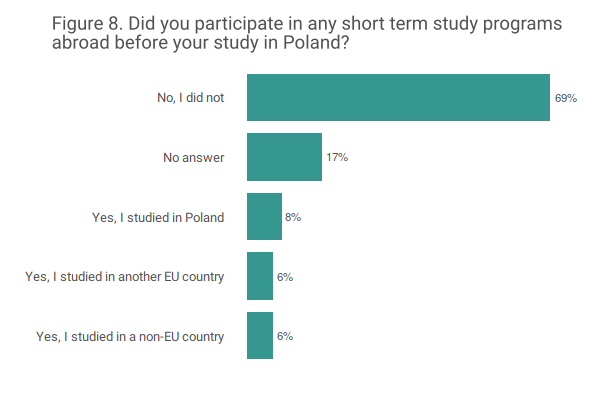

Before starting their education in Poland most of the students (69%) did not participate in any short term study programs abroad. Only 8% made it in Poland (8%), where the options of other studies outside EU and within EU – collected equally 6% of the confirmative responses.

Source: Ukrainian Students Migration to Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, the Slovak Republic: human capital perspectives, 2018. N=1055

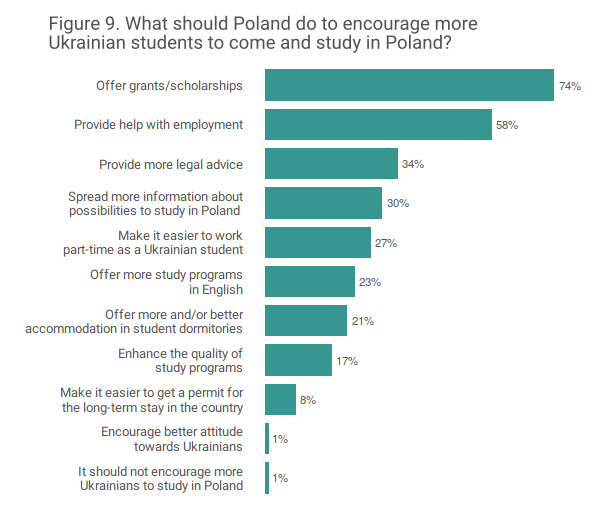

Motivating potential students to come and start their education stays the task of the university but also of the given destination country, in this case – of Poland. The Ukrainian respondents have a very clear opinion on that what should Poland do if it wants to encourage more Ukrainian students to come and study in Poland. Almost three-quarters of them point offering grants to prospective students (74%). Second most popular recommendation is to provide help on job employment (58%). These suggestions are followed by: providing more advice in legal questions (34%), spreading more information about the possibility to study in Poland (30%), making it easier to work part-time as an Ukrainian student (27%) and offering more study programs in English (23%). Offering more and/ or better accommodation in student dormitories (21%), enhancing the quality of the study programs (17%) or easier requirements to get a permit for the long-term stay in the country (8%) are perceived as important by smaller groups. Options such as encourage better attitude towards Ukrainians, it should not encourage more Ukrainian students to come and study in Poland gain around one percent of responses.

Source: Ukrainian Students Migration to Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, the Slovak Republic: human capital perspectives, 2018. N=1055

Note: Respondents were asked to choose up to 3 answers from the given list.

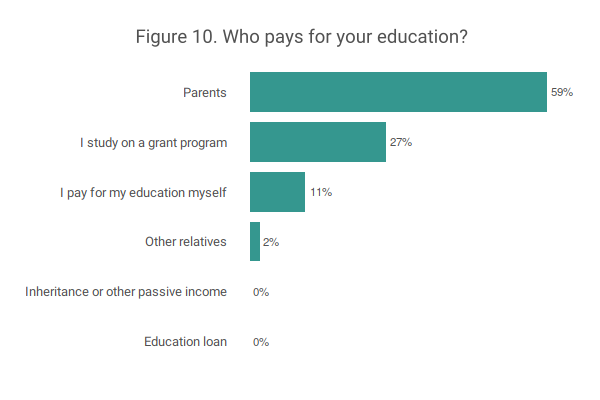

Offering grants stays as number one recommendation for the Polish country to encourage more Ukrainian students to come and study in Poland, which corresponds to the result of another question about financial sources for the their studies fees. It shows that more than half of the respondents admitted that their parents pay for their education and only 27% base their studies expenses on the grant programs.

Source: Ukrainian Students Migration to Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, the Slovak Republic: human capital perspectives, 2018. N=1055

Note: Respondents were instructed that if the payment comes from different sources, one should choose the one that covers the biggest share.

Readiness to take up employment in Poland

For the destination country such as Poland, when the lack of labor force is more and more visible, having so many foreign students might be a chance to improve the situation on the job market. However, all depends both on the preparation of the graduates to entering the Polish job market and their willingness to stay in Poland.

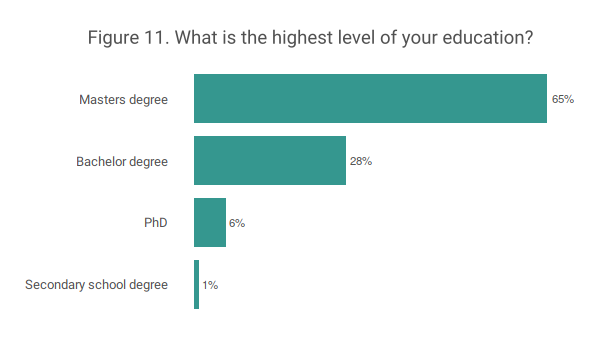

According to the graduates who participated in the online survey (183 people) their highest level of education is largely the Master’s degree (65% out of 183 respondents), the second most often chosen answer was Bachelor’s degree reaching 28% of answers. The PhD’s is the major of around 6% of graduated respondents.

Source: Ukrainian Students Migration to Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, the Slovak Republic: human capital perspectives, 2018. N=183

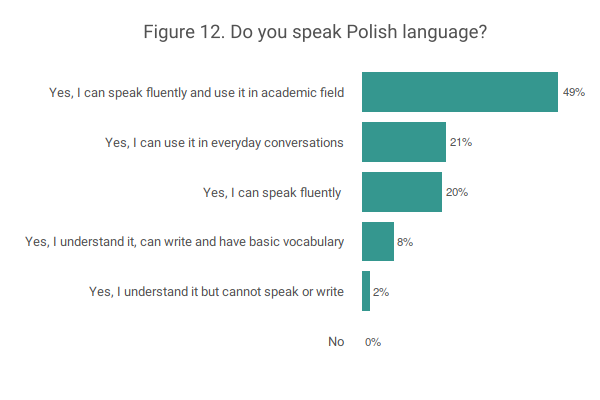

For employers looking for potential employees the language knowledge of the migrants might be a crucial aspect while taking into consideration the candidate profile. The results of the opinion polls show the level of knowledge of the Polish language among the Ukrainian students might be not satisfactory for the future boss. Even though many in Poland assume Polish is known by many Ukrainians and easy to learn for them, only 40% of the students responding the survey declare fluent knowledge of Polish in speech and within their academic area. Every fifth admit – fluency in speech (20%), the same number ability to communicate in everyday use (21%). Clear deficits in this area is declared by less than 10%.

Source: Ukrainian Students Migration to Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, the Slovak Republic: human capital perspectives, 2018. N=1055

Another factor crucial for the employers is if he/she can already get students as potential work force and if during the studies the future graduates want to get some practical experience to start directly after the graduation with a full-time professional job.

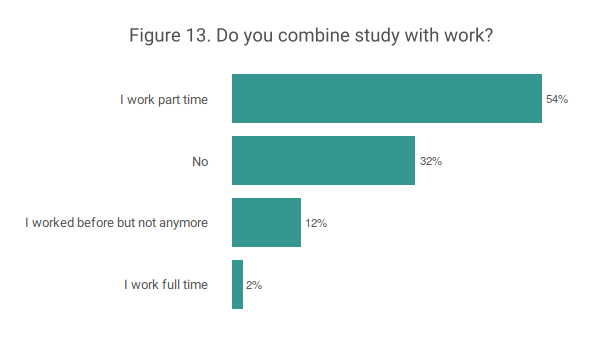

As the survey shows young Ukrainians studying in Poland mostly combine their studies with part-time job. More than half of the respondents state that they work part-time (including irregular work), while 2% of young people indicates full-time work as their occupation beside the studies. Every third person does not work during their studies at all (32%), while 12% did it in the past.

Source: Ukrainian Students Migration to Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, the Slovak Republic: human capital perspectives, 2018. N=1055

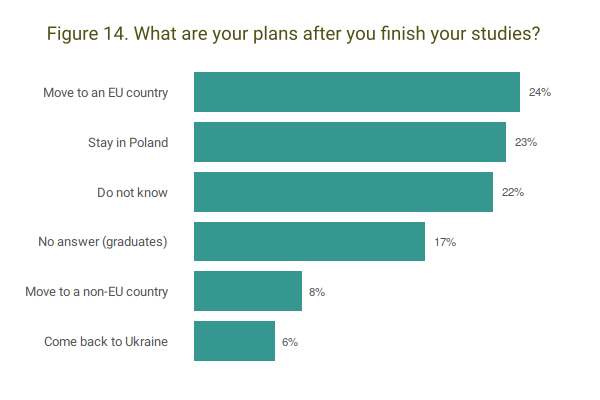

For the Polish job market it is especially important what are the future plans of the Ukrainian students. Here, the answers are very divided. Nearly the same group of respondents after graduating from a Polish university plan to move to another EU country (24%), as to stay in Poland (23%). A similar number is of whom still do not know (22%), when only 8% plan to move to a country outside of the EU. Going back to their home country seem not to be an interesting option – chosen only by 6% of those asked.

Source: Ukrainian Students Migration to Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, the Slovak Republic: human capital perspectives, 2018. N=1055

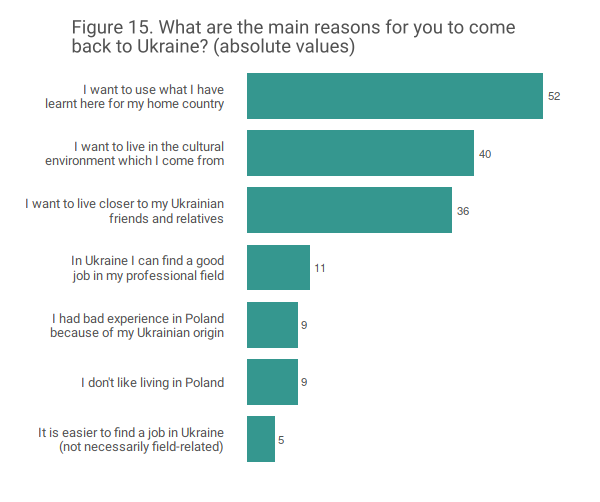

Among the reasons given by those, still very small, students considering living in Ukraine after finishing the education in Poland the most important was a willingness to use what one has learnt in Poland for one’s home country (52), secondly – living in the cultural environment which the given person comes from (40), and to live closer to their Ukrainian friends and relatives (36).

Source: Ukrainian Students Migration to Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, the Slovak Republic: human capital perspectives, 2018. N=67

Note: Respondents were asked to choose up to 3 answers from the given list.

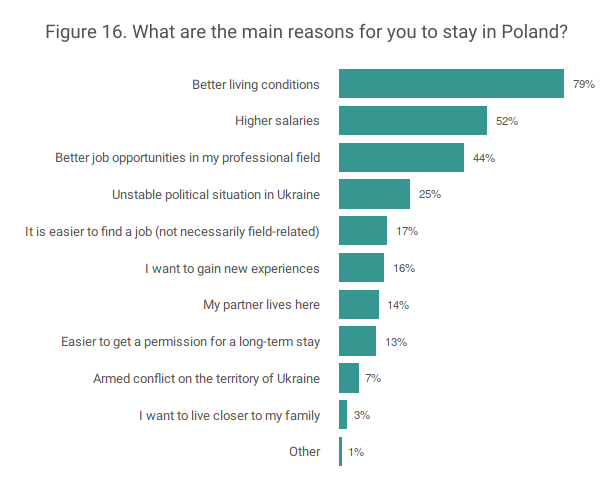

On the other hand, the ones who plan to stay in Poland (243 out of 872), at the first place state the reason for this is better living conditions (79%), the fact that they can earn more than in Ukraine (52%), and better job opportunities in one’s professional field (44%). Such reasons as unstable political situation in Ukraine (25%), willingness for the new experiences (16%), the fact that one’s partner lives here (14%), that it is easier to find a job (not necessarily field-related) – 17%, armed conflict on the territory of Ukraine (7%), and also easier to get a permission for a long-term stay than other countries (3%) are mention by a clear minority of students.

Source: Ukrainian Students Migration to Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, the Slovak Republic: human capital perspectives, 2018. N=243

Note: Respondents were asked to choose up to 3 answers from the given list.

Data coherence

Poland does not have a strategy for encouraging Ukrainian students to get their education in Poland, and still, their number is constantly growing. This is happening thanks to the activities undertaken by higher education schools, but above all, as a result of the general attractiveness of Poland as a destination country. As the surveys show, the main reasons for choosing Poland have been the relatively lower costs of living and studying compared to other countries as well as the relatively simple rules of admission to university level schools. The opinions of the interviewed experts and students are consistent. This information is crucial from the point of view of both the Polish administration, which should be interested in attracting Ukrainian students, as well as schools, for which it is also vital (an important piece of information for the latter – it is not their campaigns that manage to persuade the students, although the 7% of respondents who have been inspired by such campaigns is a number worth noting).

At the same time, the respondents clearly indicate what Poland should do if it wants to encourage prospective students to come here to study, with financial support at the top of the list. According to the data, Ukrainians, at the same time, constitute the biggest group among all foreign students who receive scholarships in Poland. However, among the respondents themselves, the biggest group are the ones whose studies are financed by their parents, which shows that even without the financial support from the Polish side or private institutions, many Ukrainians can afford to study outside their country. This should not, however, discourage Poland from seeking solutions to give a chance to study in Poland also to other young people from Ukraine. It is particularly worthwhile to invest in education in the areas that are needed on the labour market. The results of the study show that it is generally hard to hope that state institutions will seriously think about it, and especially that they will put such reflection into practice. There are no links between education planning, the labour market needs and the mechanisms that could help resolve the issue of current and future workforce deficits.

Another important factor mentioned by the respondents as the one that could encourage others to study in Poland, is support in acquiring a job. At the same time, it was this aspect that had motivated a considerable group among the respondents to come to study and – some of the graduates – to stay in Poland after getting the diploma (higher earnings, possibility of getting a job). When we compare this reply with the data showing that only every fourth interviewed student is planning to stay in Poland after their graduation and that a similar percentage of the respondents would like to leave for another EU country or that they do not know yet what they will do, it is evident where Poland can intensify its activities in order to, on the one hand, encourage people from Ukraine to study, on the other hand, to encourage them to stay and work in the country in which they have studied. The possibilities which currently exist, described in the first part of the publication, provide a good foundation that is worth reinforcing; it is also worthwhile to disseminate knowledge about these solutions, while making sure that they really work in practice, which at present is not always a case.

The hesitation of the respondents as to their future, accompanied by the belief that there is a chance to find employment in the acquired profession in Poland, is also a signal for employers looking for personnel that it is worthwhile addressing their offer to these students. At the same time, some of the students and graduates lack the crucial skill that would make them attractive on the labour market: fluent knowledge of the Polish language in their area of competence. The current personnel shortage may, however, mean that even without this knowledge the employer will be willing to offer them a job.

Generally, the great majority of the respondents (81%) are satisfied with their stay and studies in Poland. This is a reason to be glad but should also be a motivation for further action to reinforce this sentiment. Because other states of the European Union also need qualified employees, so they will be tempting such employees to go there.

Policy recommendations

Most of the difficulties mentioned by the respondents and reported in the above text are the result of the lack of the general, state-wide migration strategy that would facilitate and set the direction both for the educational and labour policies with respect to the young Ukrainians. The ad hoc measures although working in some respects are failing on the longer distance and in the wider scope. The strategic migration plan would be helpful for the sake of simplifying legalization procedures as well as eliminating burdensome financial requirements that might actually unnecessarily impede the access of some Ukrainians both to the Polish academia and the labour market. Moreover, the process of extending the legal status for the students who are already in the course of their studies should be reasonably simplified so that not to put at risk their graduation and potential future professional careers in Poland. Some revisions of visa extension procedures are due especially with respect to those students who failed some exams and hence are required to repeat an academic year – for in the current situation they risk being refused a residence permit and hence lose their possibility to continue their studies.

Moreover, the overall rationally planned migration strategy would help to develop and introduce much needed integration programs for the Ukrainian youth both in the academia and on the labour market as the experts underlined that the cultural vicinity might actually be quite misleading in this respect and leave many Ukrainian students without the proper knowledge of Polish language, that subsequently closes them on the margin of Polish society and prevents them from developing meaningful professional careers in Poland.

Beside the access to the language and other preparatory courses it seems important to further develop the system of financial support, directed to chosen, from the employers needed fields of studies.

Last, but not least, some coordination among public authorities in chargé of education, migration and labor market as well as universities is more than needed. Even though the market regulates a lot and the universities develop their own strategies to get foreign students, some joint actions would be welcome and helpful for Ukrainian young people.

References

-

ACT of 7 September 2007 on Polish Card, Dz.U.2014.1187.

-

Agnieszka Łada, Katrin Böttger (ed.), #EnagEUkraine – Civic Activity of Ukrainians in Poland and Germany, 2016.

-

Agnieszka Łada, Justyna Segeš Frelak, Medicine without borders? Qualified migrants in medical professions in Poland and Germany, 2017.

-

Jacek Kucharczyk, Agnieszka Łada, Poles vs. other Europeans, 2018.

-

Migration politics and policies in Central Europe, Globsec, Bratislava 2016.

-

P. Kaźmierkiewicz, A. Piłat i J. Segeš Frelak (ed), Przyciąganie do Polski wykwalifikowanych imigrantów. Diagnoza potrzeb w tym zakresie i rekomendacje dla polityki migracyjnej, IPA, Warsaw 2015.

-

Ustawa o cudzoziemcach, Dz.U. 2013 poz. 1650.

Support Cedos

During the war in Ukraine, we collect and analyse data on its impact on Ukrainian society, especially housing, education, social protection, and migration