Introduction

The full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 provoked the biggest housing crisis in the country’s history. By early July 2022, according to the Ministry of Community and Territory Development (Minregion), Russian troops had destroyed or damaged about 116,000 residential buildings. According to the UN, about 7.7 million people had to leave their homes and move within Ukraine. This revealed certain shortcomings of Ukrainian housing policies which had existed before. At the same time, the current crisis is also an opportunity to reconsider our priorities in housing policies and update their principles.

First of all, the war has demonstrated society’s need for social housing, meaning housing which is not owned by the people who live in it. Social housing exists to meet the need for affordable and safe housing which, for various reasons, cannot be met on market terms. Social housing is created on a non-profit basis—that is, organizations and institutions that own it do not profit from it, using the revenue to expand the housing stocks or cover the operating costs of its maintenance. Social housing can be owned both by state or municipal institutions and by private non-profits, such as charities or NGOs.

The draft Plan for the Restoration of Ukraine, presented in July 2022, recognizes that non-profit housing development must become a foundation of Ukraine’s housing policies in the future. For this purpose, it is proposed to develop a new legislative basis and improve the existing regulations. The document also emphasizes the importance of expanding the amount of housing in public (that is, state and communal, municipal) ownership and stopping the process of privatizing housing built for the funding from state and local budgets or international organizations.

Our work on this brief started before the beginning of the full-scale war. Our goal was to clarify the non-market models of the state provision of housing which remains publicly owned; to describe the system of their functioning, the opportunities and challenges in its development.

All the methods of public housing provision can be called social housing in the broad sense of the term. At the same time, in Ukrainian legislation the category of social housing does not include all the types of housing which can be encompassed by social housing as an analytical category. In view of this, for the purposes of this analysis we have categorized the methods of public housing provision into several types by the length of residence: 1) indefinite—social housing, 2) medium-term—temporary housing (up to one year with a possibility of extension),and 3) short-term—“crisis housing” (one night to several months).

The first two categories are officially listed in Ukrainian legislation as two separate types of housing stock. However, Ukrainian regulations do not feature the term “crisis housing.” Some of the types of housing which we include in the “crisis” category, such as homeless shelters, are included in the social housing category by law. Despite this, shelters are fundamentally different from other types of social housing because they do not allow for long-term residence. Just like other types of shelters, crisis housing, social adaptation or reintegration centers, they should be viewed as transit shelters which can help society to urgently respond to crisis situations, accommodate people and provide them with social aid until there is an opportunity to offer them long-term housing. In addition, the social housing system in Ukraine formally does not include publicly owned housing which has been provided for free-of-charge residence with the right to privatize it but which was not privatized by its residents in the process of mass free-of-charge privatization. Although this housing can be included in the social housing category in the broad sense, we do not consider it in our analysis.

After the full-scale Russian invasion began on February 24, 2022, Ukraine mobilized a lot of crisis and temporary housing. This allowed us to solve the urgent need for shelter for many people. At the same time, the problem of looking for medium- and long-term housing is growing. In order to solve it, we need systemic solutions based on an analysis of the current state and the starting situation with housing policies before the beginning of Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine. This brief describes the state of social, temporary and crisis housing in Ukraine before February 24, 2022.

We were able to collect most of the necessary information in November-December 2021. For this purpose, we sent public information requests to the Minregion, the Ministry of Social Policies (who redirected it to the National Social Service of Ukraine), to 24 regional state administrations (some of which redirected the requests to communities), and to the Kyiv City State Administration. In addition, we analyzed the existing regulations on social and temporary housing as well as on homeless shelters and shelters for survivors of gender-based violence. In order to verify some of our assumptions and obtain information on how the systems of social, temporary and crisis housing actually worked, we conducted 7 expert interviews with researchers and representatives of government agencies, the civil sector, and international organizations. The interviews were conducted between December 2021 and February 2022; we also conducted one interview in June 2022.

Conclusions

In the past thirty years, housing policy in Ukraine aimed to expand the institution of private property. As a result, the mechanisms of social, temporary, and “crisis” housing were developed poorly and were not a priority in public policies. The systems for the provision of different kinds of public housing work independently of one another, and there is no unified strategy for their development.

Responsibility for public housing provision in Ukraine is distributed between various government bodies at different levels. The Ministry of Community and Territory Development, which shapes and implements housing policies in Ukraine, is central among them. The State Fund for Facilitating Youth Housing Construction implements national (and, in some cases, local) housing provision programs, particularly by providing discount loans. At the same time, social and temporary housing stocks as well as various kinds of crisis housing are developed and administered by local government bodies that can also implement their own housing programs. Subventions for the construction or purchase of housing for the temporary housing stock for internally displaced persons are administered by the Ministry of Reintegration of the Temporarily Occupied Territories; the same Ministry also partially deals with the issues of housing for internally displaced persons. The issues of homelessness and gender-based violence are the purview of the Ministry of Social Policy. Thus, at the local level, departments of local governments can work with shelters as well as social and temporary housing.

Temporary and social housing stocks have been formally functioning in Ukraine since the mid-200s. Both tools are intended to provide support to people in difficult life circumstances and guarantee the right to housing for those who cannot purchase or rent housing on their own. The existence of these stocks is an important step because they attest to society’s need for non-profit housing. However, the simultaneous existence of two stocks with similar functions and goals creates new challenges and misunderstandings in housing policy. The functions of temporary housing partially overlap with the functions of social housing. These two concepts are often mixed up even by those who are responsible for their development. In the case of temporary housing, the lack of coherent legislation is an indicator of the “temporary” nature of the mechanism itself. The temporary housing system was likely meant to vanish once the social problems it aimed to tackle were solved. This approach, on the one hand, made it possible to quickly create the conditions for forming the temporary housing stock, but on the other hand, it failed to provide a coordinated and comprehensible system for the development and maintenance of this stock. In the end, despite the assumed expectations, the problems whose emergence caused the need for temporary housing have not disappeared—on the contrary, their number is only growing. Temporary housing, both as a housing provision mechanism and as housing itself, has de facto become permanent.

The administration of social and temporary housing as well as the records of the need for this housing have always been fragmented and inefficient. According to Ukrainian law, if someone does not own any housing and cannot rent it on their own, the government has to provide for their housing needs. The current Housing Code of Ukraine, adopted back in the USSR, still has a regulation on keeping the “housing queue,” that is, a record of citizens who require an improvement in their housing. Even though the record has not been kept in a centralized manner for a while now, it is still a valid mechanism through which people can receive housing from the government free of charge. As a part of the mass free-of-charge privatization procedure, they can privatize this housing within a few years. Thus, the public housing stock ends up in private hands over time. In addition to the “general” housing queue, with the emergence of temporary housing the government started keeping a separate record of people who need it, and passing the law on social housing also encoded the existence of another “queue.” The same people can be registered in all three of the queues at the same time. This creates extra workload for local government agencies and makes it more difficult to assess the need for social and temporary housing.

As of January 1, 2021, the Ukrainian social housing record listed 7,623 people, and the temporary housing record listed 4,264 people, including 2,274 IDPs. This number is probably much lower than the actual need. The process of registration can be resource-intensive; plus people are required to confirm their entitlement to social or temporary housing every year. The established criteria, the record-keeping process, and the low probability of obtaining housing lead to the situation when some of the people who need help are not registered in the queue. Some communities just ignore this need in general and do not keep a list of people who need social housing.

Social and temporary housing provision was rather decentralized, that is, local governments were the ones responsible for developing and maintaining the stocks. On the one hand, this approach allowed local governments to assess the need for this housing and develop it independently. On the other hand, they were often incapable of maintaining and funding these stocks on their own. The significant decentralization of social and temporary housing management proved to be a burden for local governments. Thus, some of the housing units could end up unsuitable for residence. In addition, the transparency and accountability of municipal housing management was insufficient. Even though the mechanism of public supervision of housing distribution existed, there were no special procedures for public participation in housing management. These mechanisms could include supervisory or public councils, or resident unions representing their interests.

In general, there was not enough sustained investment in social and temporary housing stock at the national level. That is why the number of housing units in these stocks was low. Communities had to adopt programs with minimum effectiveness, look for short-term aid from international donors, plug the gaps in one stock at the expense of the other.

In the past few years, funding for developing temporary housing stocks was allocated from the state budget via a targeted subvention to local governments. This was one of the main mechanisms for growing the stocks. However, it also had its limitations, because under the conditions of regional inequalities not all communities had equal opportunities to use the subvention. At the same time, no centralized state funding for the development of social housing was allocated at all in the past few years.

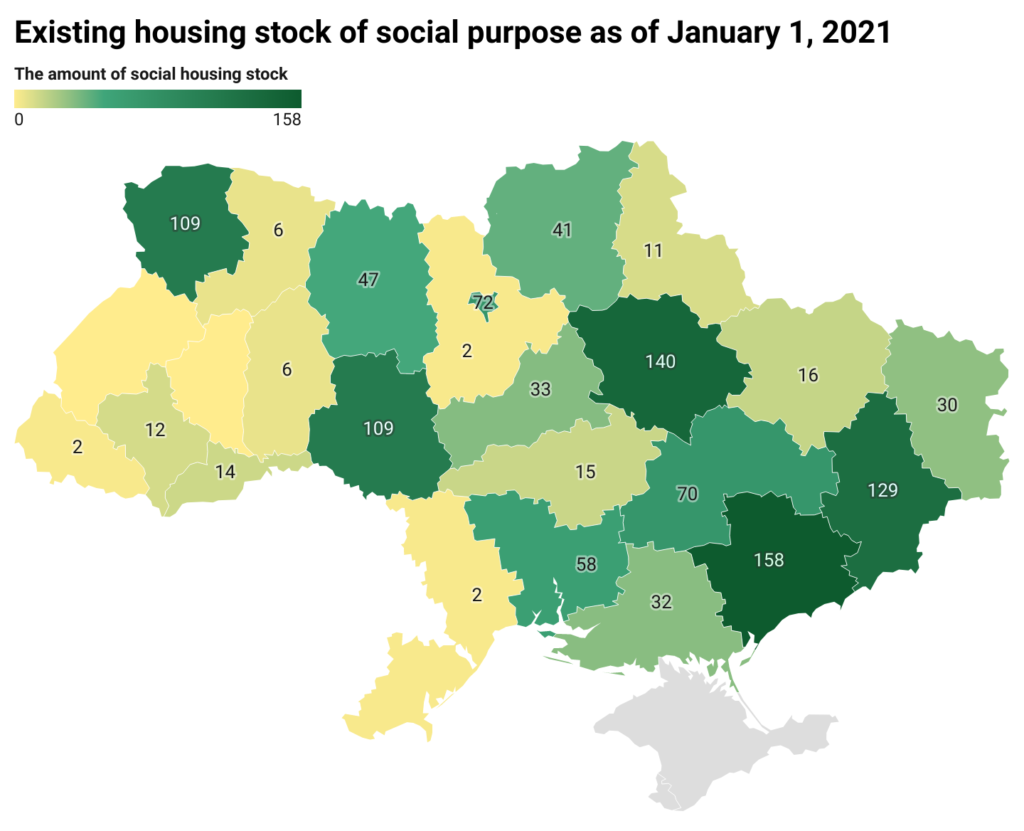

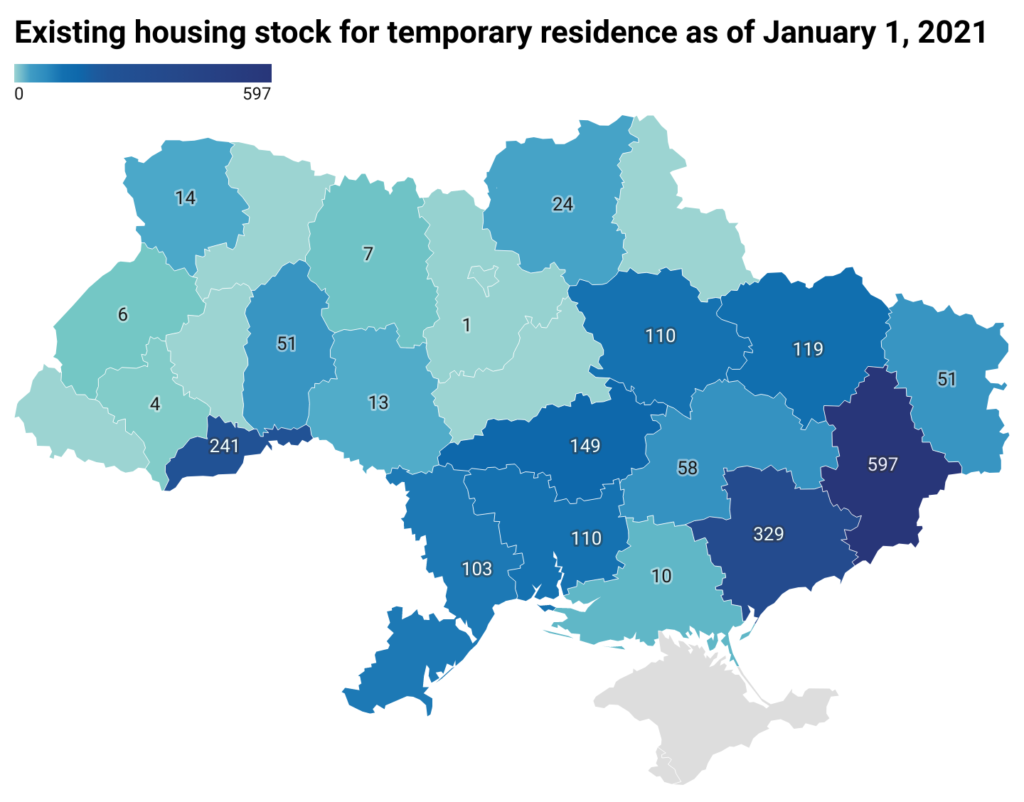

As a result, the social and temporary housing stocks were small. As of January 1, 2021, there were only 1,098 units of social housing and 1,997 units of temporary housing in Ukraine in total. Unfortunately, a significant share of this housing has ended up in the temporarily occupied territories after the full-scale war began. For example, the highest number of temporary housing units in Ukraine were located in the Donetsk and Zaporizhia Regions, and Mariupol was one of the leaders in developing its housing stock after 2012.

Marginalization of social and temporary housing was embedded in the system proposed by the current legislation. This housing is intended exclusively for “socially unprotected categories” (which later also de facto included internally displaced people), some of whom also need social services. The existing social and temporary housing is sometimes in a poor condition or has no shared spaces or individual rooms for all the residents. The issue of integration of the people who live in this housing into the community are also often ignored. Both at the national and at the local level, people who apply for social and temporary housing are viewed as a “problem” that needs to be “solved,” in contrast to other people who can afford to rent or buy housing.

Ukraine also has housing which we label as “crisis housing,” even though this term does not officially exist in Ukrainian law. Its main purpose is to provide short-term shelter and support to people in an emergency. To achieve this goal, crisis housing must be integrated with other public housing provision systems, e.g. with the social and temporary housing system. When the period of living in crisis housing ends, a person may need different, long-term housing. However, this transition did not usually happen in Ukraine. Reasons for this include the fragmented nature of housing policies, scattered responsibility for different types of housing among different government bodies, and insufficient social and temporary housing stocks.

Just like in the case of social and temporary housing stock, responsibility for “crisis” housing was borne by local governments. In the case of shelters for survivors of domestic violence, this system was successfully developed and improved in the past few years thanks to a subvention from the state budget and support from international organizations. However, the number of such shelters is still insufficient and does not allow to fully meet the need for them: in July 2022, there were 40 shelters and 33 crisis rooms in Ukraine. Meanwhile, the system of homeless shelters in Ukraine is not developed properly, and the problem of homelessness does not receive proper attention from local and national government bodies. In 2020, 8,057 homeless people were registered in the entire territory of Ukraine, while various facilities for them only provided 1,765 spots. And the real number of homeless people can be much higher, according to volunteers and NGOs.

In general, the state system for housing provision in Ukraine includes tools which are supposed to guarantee the right to housing for people who, for whatever reason, cannot meet their need for housing through market mechanisms. In theory, this approach involves a system of steps according to which, for instance, a homeless person first receives “crisis” housing, such as a bed in a shelter, and then they will be able to receive temporary or (later) social housing in which they will live until they are able to rent or purchase housing on their own. However, the transition from one type of housing to another usually does not happen because different mechanisms are not coordinated properly, are inconsistent or poorly developed.

The described system of social as well as crisis and temporary housing in Ukraine today matches what Jim Kemeny labels as the dual model in his categorization. This is the cause of some of the shortcomings described above. Here are the main features of this system:

- the stocks are owned and managed by central or local government bodies;

- the stocks are formed as an afterthought;

- the stocks exist to meet the needs of low-income people, and the distribution of housing depends on income;

- to receive housing, one has to pass a complicated bureaucratic procedure.

Since people are less likely to support government programs whose products they themselves cannot use, social housing in dual systems is often underfunded and therefore remains in a poor state. Thus, the treatment of residents of social housing is paternalistic, they are viewed as people who cannot help themselves and need care.

In contrast to this system, Kemeny identifies the so-called integrated model which he deems more effective. The foundations of this system could serve as a theoretical basis for updating the housing policy in Ukraine. The main features of this integrated model include:

- the stocks are owned and managed by both public or municipal companies and private owners (housing cooperatives, associations, non-profits) which create social housing on a non-profit basis;

- the housing can be claimed by broad groups of people, not only the most vulnerable;

- since the housing can be claimed by broad groups of people, the procedure for obtaining it is simplified, and marginalization of this housing can be avoided;

- since social housing is integrated in the housing sector, it “competes” on the market with other types of rental housing and therefore indirectly affects the price and establishes the desired standards of rent in the for-profit sector.

Of course, we should distinguish between short-term and long-term goals for the development of social housing in Ukraine. Today, in the conditions of the war and a housing crisis, the main goal is to guarantee the right to housing for the most vulnerable groups of people. The first priority is to provide housing to everyone who has lost their homes as a result of the war and cannot provide themselves with other housing on their own. For this purpose, we should expand publicly owned social housing stocks and build an effective and coordinated system for managing them. This system, on the one hand, will give local governments enough opportunity and power to manage this housing, and on the other hand, will guarantee stable financial support for the development of social housing from the central government. In the future, access to social housing should be extended, and conditions for engaging non-governmental actors in the construction and maintenance of this housing should be created.

Suggestions

- Combine the social and temporary housing stocks and create a unified publicly owned social housing stock.

- Create a Unified State Registry of Citizens Who Need an Improvement of Housing Conditions instead of a range of separate lists and “queues.”

- Reconsider the criteria and procedures for the provision of social and temporary housing so as not to exclude anyone who really needs help with housing. It is worth abandoning the practice where people have to work to collect references about information which could be obtained by integrating public registries, providing access to them, or by interdepartmental cooperation. At the same time, in order to make this possible, record-keeping bodies must have sufficient resources to hire as many people as necessary to accept and process all applications.

- Improve the system of social housing management at the local level, particularly by creating dedicated communal institutions, further professional training, creating opportunities for international exchange of experience, and spreading best practices.

- Improve the transparency, participation and accountability of the social housing management system not only at the stage of housing distribution but also at the stage of management, particularly by creating supervisory boards and unions of residents of social housing.

- Adopt a state social housing development program and increase state support for communities so they can effectively develop and manage their social housing stocks. In particular, funding should be provided to develop social housing, including via the subsidy mechanism.

- Create a Unified State Registry of Social Housing which will encompass the information about all the available social housing in Ukraine.

- Consider the issue of appropriateness of determining/creating a single government body that will be responsible for social housing at the national level, particularly for administering state funding, collecting and publishing information about the need for housing and the number of housing units. Possible options to consider include repurposing and updating the State Fund for the Facilitation of Youth Housing Construction for these functions, or establishing a separate Ministry of Housing Policy (which can also take over the issues of utilities and housing maintenance).

- Develop and adopt a new Concept of State Housing Policy in Ukraine and update other housing legislation on its basis. Among other things, the new housing policy must pay attention to the system of state housing provision for those who cannot meet their need for housing on market terms, without the right to privatize housing received from the state. The need for social housing should be viewed not as a temporary problem which is possible to solve in the future but as a permanent and integral part of the housing provision system in Ukraine. In addition, the program should also address the problem of homelessness and include measures aimed at reducing and preventing homelessness.

- Develop a concept for the development of the crisis housing system in case of emergencies and natural disasters which has to be integrated with other types of housing in order to provide people in need with all the necessary support and opportunities to move from short-term to affordable and decent long-term housing.

- Develop the system for the monitoring, assessment, and methodological support of shelters and crisis housing facilities, particularly in order to collect data, spread best practices, share experience internationally, provide further professional training.

- Increase the inclusivity of government aid to people who need crisis housing, particularly by reconsidering the existing rules and procedures and by providing government support and funding to NGOs which provide help and shelter to certain social categories.

- Provide support, particularly financial support, to communities for developing the system of aid and crisis housing for homeless people, particularly via the subsidy mechanism.

- Continue and intensify state support for communities for the purpose of creating a crisis housing system for survivors of gender-based violence, particularly via the subsidy mechanism.

Support Cedos

During the war in Ukraine, we collect and analyse data on its impact on Ukrainian society, especially housing, education, social protection, and migration